I grew up in the thirties during the Great Depression in a suburb of New York City. My mother was an adequate cook, but stuck mostly to roast chicken, meat loaf, and pot roast-type meals. I don’t remember her ever serving any fresh fish or shellfish to

our family.

It became my fate to end up on an island, surrounded by fish and shellfish, not to mention wild ducks and geese, and even venison. In 1946 when I first came to the Vineyard, between my sophomore and junior years at Brown University, I got a waitressing job at the Edgartown Café, now known as The Wharf. One night I served a table for two, and the couple turned out to be Dorothy McGuire, a rising Hollywood star, and her husband, John Swope, a Life magazine photographer. During our conversation, and while I served them two boiled lobster dinners, she discovered that I had never tasted lobster. She kindly left me a $2.50 tip with a note suggesting that I use it to buy a lobster dinner. At the end of the summer and my tenure as a waitress, I went back to the café as a patron and ordered a lobster dinner. My first – but I have yet to eat my last.

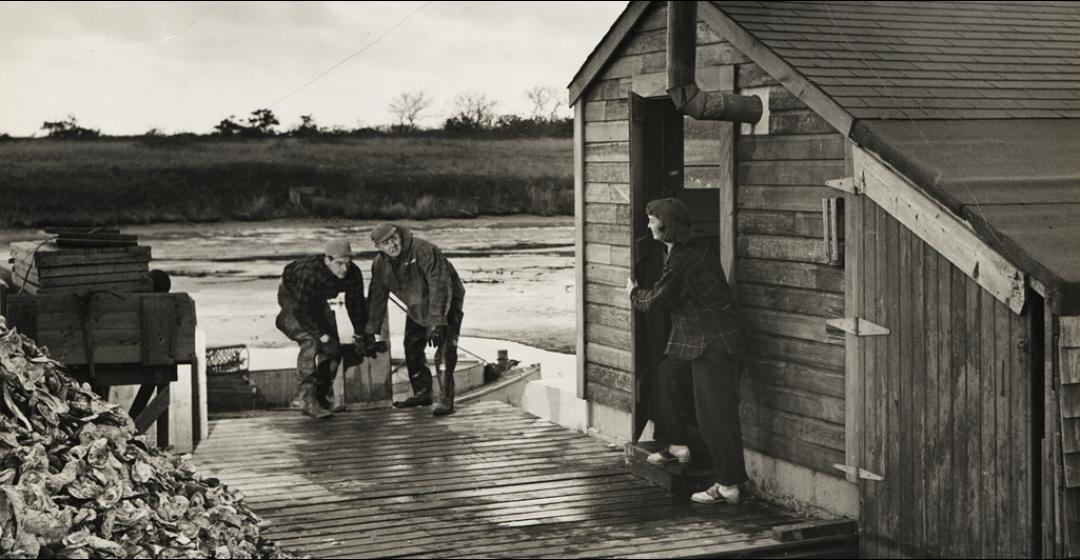

My tastes were about to be tested. Johnny, my husband, was not a commercial fisherman, although we spent the first nine years of our married life growing oysters in Tisbury Great Pond. I learned to eat them, not enthusiastically at first, but the taste grew on me, especially when Johnny started making delicious broiled oysters and oysters Rockefeller. I learned how to make a superior oyster stew that proved popular with dinner guests.

While oystering during those early years on Tisbury Great Pond, Johnny started setting pots to catch eels as there was a good market for them in Boston. I drew the line at cooking an eel, however, and so have never tasted one. And when he started bringing home blue claw crabs – by the bushel – and we sat up until two a.m. cooking them and picking out the sweet meat with tiny picks, I wasn’t feeling so anxious for a crab meat meal. So I would freeze the crab meat until I had forgotten the pain of getting it ready to eat, and then I would enjoy crab salad.

Years later, when Johnny set a family limit of ten lobster pots out of Menemsha when local lobsters were plentiful, someone in our family of five was heard to say, more than once, “What! Lobster again?” On the other hand, when I wanted to treat my fellow female teachers to a beach picnic, I would tell my husband that I needed eighteen lobsters in order to make lobster salad for twelve friends – and he would get them for me. Good memories for me now that lobster is scarce on my dinner plate.

About the only thing I contributed to the hunter/gatherer tradition in our family was to collect grapes and beach plums in the fall for jelly, and I did this for many years. I would stock a shelf in the basement each fall with thirty or forty jars of jelly – grape, beach plum, occasionally crab apple – to last us until the next fall.

We were “eating local” back in the 1950s – we just didn’t realize it. We ate what the stores sold, when we could afford it, and were dependent upon what our men could harvest from the sea and the land and the sky. We were young and just starting out, and we ate a lot of tuna fish casseroles and meat loaf. But we had vegetable gardens and we fished and we hunted, and I guess that meant we were “eating local.”

Farmer Arnie Fischer would deliver eggs from his chickens to our kitchen door for about fifty cents a dozen. They were local eggs. A dairy farm was started in Edgartown by Bill Pinney. It picked up the raw milk from all the farmers who had cows, pasteurized it, and then delivered it to us in glass bottles. That was our local milk.

Oystering was a good life for Johnny – hard work in the outdoors while he adjusted to civilian life after almost four years as a Navy fighter pilot in World War II – but it didn’t provide us with a real living wage. We did eat a lot of oysters, and we had our own business, Vineyard Shellfish Company. Free oysters were a perk of growing our own, and I guess they were good for us. We had three fine children during those years.

We depended on the hunters in

our crowd to provide meat for the table. Johnny had been a sport fisherman all of his life before I met him, and after we married, from spring until fall, we ate lots of bluefish and striped bass. His cousins, John and Everett Whiting, were mainly hunters of ducks and geese, so our diet varied as we shared dinner parties. There wasn’t much variety in cooking bass and bluefish, except back then there was no size limit on the fish caught. We were able to bake a whole bass, with a flavored bread-crumb stuffing, when it was small enough to fit into our oven. In those early days of the 1950s, striped bass were plentiful. It was a rare treat when Johnny caught a bluefish.

By the 1980s the striped bass population had dropped dramatically, but there were many more bluefish to be caught. Louise Tate King, who co-authored The Martha’s Vineyard Cookbook in 1971, taught Johnny how to smoke bluefish, and from that came a delicious smoked bluefish pâté. Both were added to our menu when we had company. Although I would always be considered a “wash-ashore,” after a few years of eating food from the land and the sea, I was beginning to feel like a “Vineyard girl.”

We had been attending wild duck dinners at Everett Whiting’s house for a number of years. The problem for me was that Everett’s idea of preparing a wild duck was to pass it through a hot (500 degrees) oven. I couldn’t stomach the bloody meat that appeared on my plate, so I usually just ate the rice and salad. But when Johnny and Stan Murphy began shooting their own ducks from blinds on Black Point Pond and Tisbury Great Pond, I discovered they could be delicious if I cooked them for at least thirty minutes. And I also discovered that certain ducks tasted better than other kinds of ducks. We liked Canvasbacks the best. As most duck hunters would agree, the taste of wild ducks depends mostly on their diet. Canvasbacks are mostly vegetarians. The worst tasting duck, in my opinion, is the Sheldrake. It is a fish-eating duck and Johnny, who didn’t like to waste anything, would slice off the breast meat and sauté it. I wouldn’t touch it because it tasted like bad liver. The rest of the duck was thrown away. Stan said even his dog wouldn’t eat it.

When we lived across the road from Everett Whiting’s farm (from 1948 to 1957), I planted a small vegetable garden on the north side of the house – not very convenient for harvesting as all the doors in the house were on the south side. But I could see it out of the dining room window. Johnny built a wire fence around it to keep out the rabbits – not high enough to keep out the deer, but then, we never saw any deer around to keep out.

One day, however, I glanced out my dining room window and saw one of Everett’s cows standing close to the fence. As I watched, she leaned in, put her head down and began munching on the emerging lettuce. I yelled to Johnny, “There’s a cow eating my lettuce!” He reacted quickly, without thought, grabbed a broom and ran out the kitchen door. As he ran around the back of the house to reach the garden, he was threatening the cow in a loud voice and waving the broom. The frightened cow reacted quickly, also without thought, and gave one mighty leap over the fence and into the garden. Then she raced around in a panic trying to get out of the fenced-in garden and trampled everything she hadn’t eaten. I think that was my first and last attempt at a vegetable garden.

Johnny, however, took up gardening in the sixties when we were in our

new house off Music Street. He grew enthusiastic in late winter when the hunting season was over and the bass and bluefish had gone south. The seed catalogs began to arrive in our mail box at Alley’s in March – some even in February. He would spend his evenings poring over them, comparing varieties of tomatoes and lettuce. Should he get Big Boy tomatoes or the Beefsteak variety? And maybe some of the yellow cherry tomatoes – and of course some zucchini. Almost every gardener grew zucchini and they were hard to give away when they all came ripe at once. We were warned early on to always lock our car when parking in Vineyard Haven in August – not because a tourist might steal something from us, but because a Vineyard farmer might fill our back seat with his extra zucchinis. No point in growing zucchinis – we would just leave our car unlocked downtown and we might receive the leftovers from someone’s garden.

For almost ten years Johnny went swordfishing out of Menemsha in the summers. Once in awhile he would bring home a small swordfish or part of a larger one, cut it up, and freeze the steaks for future meals. We might have been poor, but we ate well. And unlike myself, deprived of seafood as a child, my children grew up on a diet of food from the pond and the sea.

Today we have the West Tisbury Farmers’ Market, which extends into late fall, local fish markets, and Morning Glory Farm, which has expanded from fields of vegetables into homemade baked goods and homegrown chickens and beef. We also have about thirty small farm stands and even a famous shop in Chilmark that turns out homemade chocolates. Linda Alley makes and sells a wide variety of jams and jellies, so we can still eat “locally” – but we don’t need to do it all by ourselves.

This essay is an excerpt from Looking Back: My Long Life on Martha’s Vineyard (Music Street Press, 2014).