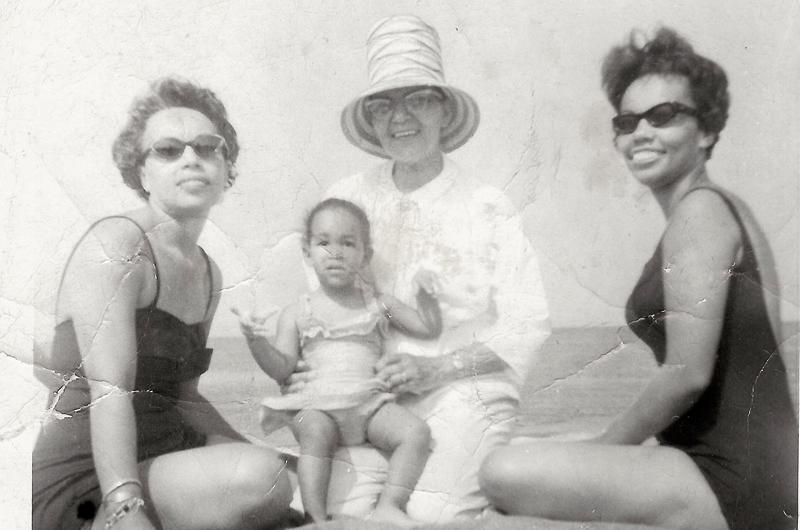

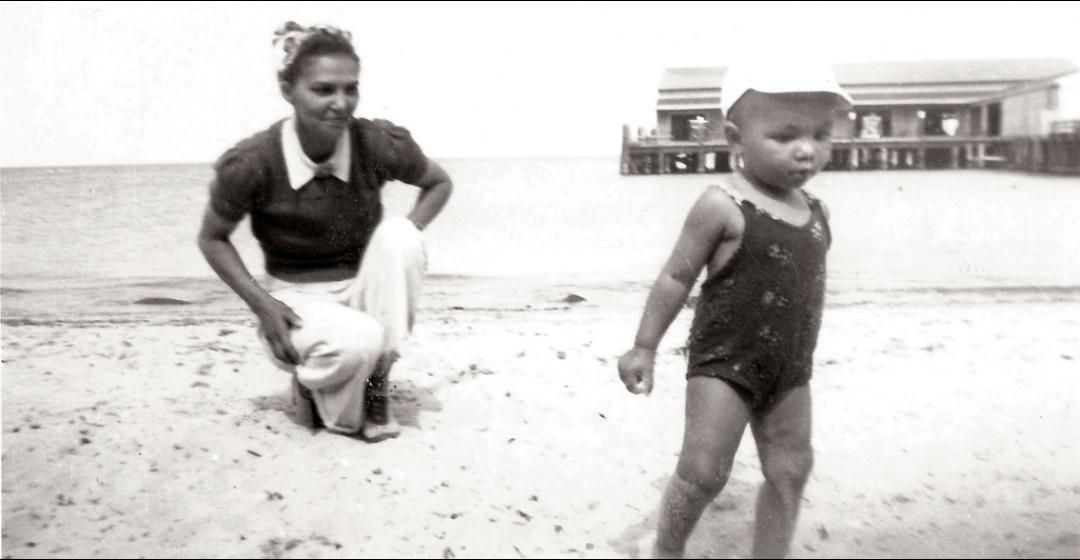

Nearly ninety years ago, in 1927, my paternal grandmother, Luella Barnett Coleman, came to work on the Island as a waitress-domestic. My father, J. Riche, was nine at the time and my aunt Leona (Nonie) was three, and for a number of years, Granny boarded them with Island families in Vineyard Haven and in Gay Head while she worked cleaning the homes of summer residents. In the late 1930s, however, she began to rent a small cottage at the corner of Laurel and Moss Avenues in the Highlands of Oak Bluffs, and in June of 1940 I arrived with my mother to spend my first birthday and the summer. With the exception of one summer in 1964, I have been here every year.

The Highlands is an area in the northeast corner of Oak Bluffs that was originally laid out in 1869 by the Vineyard Grove Company as part of a plan for Cottage City. Though not specifically designed as a neighborhood for black vacationers, Robert Hayden and his daughter Karen suggest in African-Americans on Martha’s Vineyard & Nantucket that the construction of a wooden open tabernacle in 1877 – on a site where the New England Black Baptist Association had held meetings for years – “contributed to the Highlands becoming the first summer neighborhood for vacationing and homeowner Blacks in the early 1900s.”

The neighborhood was therefore already established in 1944 when my grandparents purchased land on Myrtle Avenue from Manuel Gonsalves. On the three-lot property there was a cottage that had a living room, kitchen, four bedrooms, and one little bathroom that measured about three feet by five feet. It was only large enough for a sink and a “commode,” as my grandmother euphemistically called it. Granny shuddered at the use of the word “toilet.” On one of the other lots was a barn with a sand floor. They paid $800 for the whole purchase.

A few years later, Mr. Gonsalves approached my grandmother and said that he was selling the two remaining lots on our side of Myrtle Avenue and wanted her to have first option. My grandfather’s passion was the theater, but he was a presser by trade in the garment district of Boston. My father, meanwhile, was an underpaid social worker and my mother worked in department stores. Obviously, we were not a family of means, but Granny had a reputation for keeping her word and paying her bills regularly. She wasn’t interested in becoming a land baron, but she coveted the privacy and protection of her family. So she purchased the two adjacent lots with the promise to Mr. Gonsalves that she would give him, in her words, “A nickel down, and a nickel when you catch me.” In 1955 she purchased three more lots on the opposite side of the road, with the intention that her son and daughter would eventually be able to leave land to their own children.

Myrtle was, and still is, a special street. Isabel Powell, first wife of Congressman Adam Clayton Powell, lived on the corner. She was in show business and never lost her sense of the dramatic. She had been a dancer at the Cotton Club and had a starring role in the Broadway play Harlem when her husband met her. After they divorced, she became a special education teacher. The house next door to hers was owned by Celestine Bayne and her sister Doris W. Jones, who founded the Jones-Haywood School for Ballet in Washington, D.C. Two houses away lived the author Dorothy West, while across the park lived Irene Ford, who taught at Howard University until she was well into her seventies. Two doors down from her was Maxwell House, a bed and breakfast whose major competition was Shearer Cottage, which is just up the hill from the northern end of Myrtle Avenue.

Across the road from Maxwell House was the home of Thelma Garland Smith. According to an historical account by Dorothy West, she was inspired to organize a club to work for charitable causes after overhearing someone’s observation that black people rarely took part in community affairs. In 1955 a group of eight ladies met on Smith’s porch and the idea of the Cottagers was born. The following year, after meeting “officially,” they donated $380 to the Martha’s Vineyard Hospital. Since then, the Cottagers have donated from $5,000 to $12,000 each year to various charities and scholarships.

My grandfather, Ralf Meshack Coleman, meanwhile, was a renowned actor, playwright, producer, and director who travelled throughout the U.S. in these capacities. He starred in 1934 on Broadway as the romantic lead in Roll Sweet Chariot, and later toured with Anna Lucasta. In 1935, he became the first black director in President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s WPA Federal Theatre Project, and in 1965 founded the Negro Repertory Theatre, which performed throughout New England. In 1975, a year before my grandfather’s death, Mayor Kevin White called him the “Dean of Boston’s Black Theatre” and proclaimed October 5, 1975 as Boston’s Ralf Coleman Day.

Initially, my grandfather was not happy about Granny’s multiple land purchases on the Vineyard, but eventually he came to love our little corner of Oak Bluffs. He proudly named it Coleman Corners and had a sign crafted to identify it as such. Active in summer theaters in Provincetown and Oak Bluffs, he often held cast parties at Coleman Corners.

As an adult I feel privileged to have known these accomplished African Americans so intimately, but when we were children all we knew was that the adults in our neighborhood were nice to us, offering brownies still warm from the oven or grapes freshly picked from a backyard arbor. They let us play in their yards, catching fireflies at night and in their homes on rainy days. They let us set up camp in their park – that is to say Dottie’s Park, formerly known as Asbury Park, and referred to as “The Oval” in Dorothy West’s book The Wedding. We knew that we were expected to show respect for neighbors and property and to mind our manners or Granny would hear about it.

Looking back, I have to marvel at Granny’s determination and vision. She did it all by working menial jobs and probably secretly redistributing whatever allowance my grandfather gave her to manage their apartment in Boston. She was famous for her baked beans, fish cakes, yeast rolls, and apple pie, and she served them to friends who were invited to visit Coleman Corners with their families for a long weekend. Some of those families returned to buy property so they could experience their own love affair with the Island.

Today, many people who vacation on the Island, even those who have owned homes in Oak Bluffs for years, have no idea where the Highlands is. We kind of like it that way; we like our privacy. A number of years ago, tour buses started coming through the neighborhood. One day my aunt Nonie happened to be outside, wearing a bandana while working in her yard. As a large tour bus lumbered toward the end of Myrtle Avenue, she walked out into the middle of the road, planted her feet firmly in the sand, and stood there waving at the bus to stop. I am sure the patrons on the tour bus thought they were about to get another piece of history as they toured the sites on the African American Heritage Trail. Perhaps this black woman, head wrapped in a bandana, was going to enlighten them about the history of slaves on the Vineyard.

Well, they didn’t know my aunt. The bus stopped, the door opened, and when Nonie got on she proceeded to tell the driver in very strong terms that this was a private residential neighborhood where children play in the roads, that the sandy roads weren’t big enough for the buses, and this wasn’t a tour route. And if she saw any more tour buses coming down Myrtle Avenue, she was going to go to the authorities and put a stop to it. Without waiting for a reply from the bus driver, Nonie turned around, straightened her bandana, got off the bus, and went back to her work in the garden. Needless to say, to this day we have never seen another tour bus on Myrtle Avenue or any other abutting roads.

But we are also a caring neighborhood. We call out to those drivers who appear to be going too fast down our sandy roads where children play, and we come out of our homes to offer directions for those who don’t know how to get back to “civilization,” as one lady recently put it.

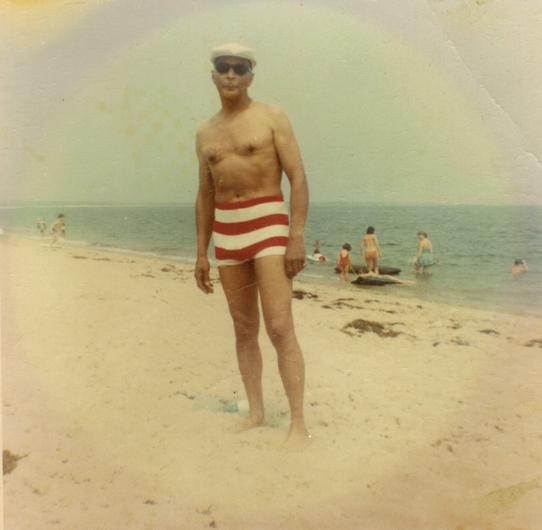

By 1946 there were five Coleman grandchildren: four girls – me, Marcia, Gretchen, and Stephanie – and one boy, Jay. Granny remained determined to bring us to the Island for the whole summer, away from the hot, humid streets of Roxbury. She always took jobs in Boston that allowed her to leave for the season, and I remember her telling me that her employment often depended on whether the employer realized that she was black. Being biracial, she was sometimes mistaken for white, and because she was very good with numbers would be hired as a salesperson in downtown Boston department stores. Other times, when they recognized her as African American, the only job she could get was running the elevator. Granny had only a high school education, but whatever her employment, she always carried herself as a “very proper Boston lady.”

The day after school closed in June, we would pack into her old Woodie station wagon loaded down with five kids, Sheba the dog, plants, and boxes of whatever necessities Granny had collected over the winter. One year there was even a wooden door tied to the top of the car. Then, Monday through Friday all summer long, we walked the half-mile to Vacation Bible School at the Tabernacle in the Methodist Camp Ground. Children of all races came from all over the Island to that program, where we heard Bible stories, sang hymns, and made crafts, my favorite being the wind chime made from a metal mayonnaise jar top and long, thin pieces of glass that we decorated.

At noon we returned home to do our chores, fix peanut butter or bologna sandwiches for lunch, and then begin our walk to the Inkwell. Our route invariably took us behind the Wesley House, where we sometimes got lucky when a baker would hand us freshly made doughnuts, which I guess you could call the town’s first “back door donuts.” From there we went on through the Tabernacle grounds, across Circuit Avenue, through Ocean Park, past the “pay beach,” and then down the steps to the Inkwell.

We played in the sand with friends, cannonballed off the pier, swam to the raft, dug up clams with our toes, cracked them on the rocks of the jetties, and ate them raw. Often we swam over to the pay beach, where we would tread water and wave at the folks on the beach, just for the heck of it. We were all swimming in the same water and they had paid twenty-five cents each day to do it. Wednesday evenings we went to the Community Sing at the Tabernacle, where we enjoyed singing rounds like “Row Your Boat” and “K-K-K-Katy (Beautiful Katy).” That was summer. And on Labor Day we would return to the city, tanned and happy. The streets of Boston seemed so small, the buildings so unyielding and massive, smothering us after a full, free summer on Martha’s Vineyard.

As we became teenagers, we took jobs on the Island to have spending money.

I remember babysitting, cleaning houses, and tutoring mathematics, all for fifty cents an hour. But a half pint of fried clams cost only fifty cents so I felt rich!

Those early and teenage years were carefree. Friendships were made that continue to this day, first loves and breakups were experienced, and we played and partied together with no sense of class or stature or the accomplishments of our parents. As new kids arrived each summer, we welcomed them into our crowd, neither knowing nor caring what their parents did for a living nor how much money they made. And to this day we share a history of coming of age on this wonderful Island. We hung out at the Inkwell during the day and walked up to the boat wharf in the afternoon to watch the guys coin dive. My aunt, now ninety-two, has told stories of how she also coin dived when she was a teenager.

In the evening, we went to the roller skating rink in the old Tivoli building where the police station now stands, or we spent time at the Herald Drug Co., where Reliable Market is today. As long as we bought a Coke or a frappe and weren’t too noisy, Freddie, one of the owners, allowed us to play the jukebox and practice dance steps in preparation for the house parties during the weekend.

Sometimes we even snuck down to the pay beach and went skinny-dipping, asking one of the younger girls to warn us if the boys came along. As long as we were on our way home by the time the drugstore closed, we were able to come out the next night. But if we tarried without a good excuse, we were grounded for a few nights. We called ourselves the Hound Dogs. All of these experiences bound us together, and as adults we have even had Hound Dog reunion weekends. Life could not have been more perfect.

Although my aunt and father have told us stories of deliberate slights and bad experiences on this Island due to their being black in the 1940s, I personally recall only instances of subtle discrimination. In spite of being an honor student and the first black senior class president in the history of my high school, I could only find work washing dishes at LaBelle’s Bakery on Circuit Avenue. Better paying jobs on the Vineyard, like being a waitress or salesperson, were not available to us, so for the next four years after finishing high school in 1957, I came to the Island exclusively on weekends. I had to earn money for college.

After college, I returned to Coleman Corners for a few weeks each summer to spend time with Granny. As an adult I had many interesting conversations with Dorothy West about gardening, feeding birds, and writing. After reading The Wedding, I remember asking her about the similarity of “The Oval” to the park in front of her house and of some of the personalities she developed to people we knew. After all, the featured family name in the book was the Coles, and our name was Coleman! While I don’t recall her exact words, I do remember her message and her rapid pattern of speaking: “Well, you see, my dear, that writers take what they know and then, you see...they transform it and add on and so on and...so, my point, dahlin’, is...that’s what makes one a writer.”

And I enjoyed an especially warm relationship with Isabel Powell, who loved my grandmother. After Granny died at Windemere Nursing Center in 1996, one month after her one hundredth birthday, Isabel and I often sat on her porch drinking her famous – and potent – Bloody Marys and sharing stories about those special times we had spent with Granny. Isabel made brownies early in the morning for visitors and especially on Wednesday mornings for the trash men. I often wondered if those brownies saved her from having to purchase a few trash stickers. Even into her nineties, she was very vocal about her opinions and loved to talk about current events – and she was fiercely proud of President Barack Obama. On one occasion, I complimented her on a lovely silver heart-shaped necklace she was wearing. The next time I visited her, she handed me the necklace – given with love.

Today, my grandmother’s original house still stands, but with an additional bedroom, a second bathroom, and a shower that we installed after much negotiation with Granny. The house is now owned by my sister Marcia and her husband, Hewitt. The barn was transformed into a cottage by my carpenter brother, who lived there year round for more than thirty years. As for me, I have now come full circle: my husband Duncan and I are retired here, in a house we built on the very same corner property that Granny bought in 1948. Each summer our children and grandchildren visit, thus becoming the fourth and fifth generations of Colemans to play in the sandy road that is Myrtle Avenue, take walks in the woods, and swim at the Inkwell just as our grandparents, father, and aunt

did so many years ago.

Over the years, there has been a popular conception about Oak Bluffs being the center of the African American “elite,” as evidenced by a recent article in Town & Country magazine on the topic. Certainly, as more upwardly mobile black families have discovered the Island, that demographic has increased. In an article about Oak Bluffs in the June 2003 issue of National Geographic, someone was quoted as saying that you must have a “certain pedigree to be here.” However, African Americans from all walks of life and all levels of financial status, whether celebrity or not, visit and live here to enjoy the beauty, the peace, the camaraderie, and the freedom this Island offers. The Coleman family and many other working-class families were fortunate to grow up spending summers here in obvious contradiction to that belief.

Those of us who are third, fourth, and fifth generation have been especially fortunate because of the vision of our parents and grandparents. We are here because of the legacy they left us.

Looking back, I’m awed by the humility of the people in our small “village” as they dealt with us as children. Our little piece of the Highlands provided us a sense of self that we might never have had without the opportunity to thrive in this community of acceptance. And so we recognize our responsibility to pass on a sense of stewardship to our children and grandchildren lest the legacy be lost.

Spending summers here as children meant that no matter where we lived or traveled in life, coming back to the Vineyard, the Highlands, and especially to Coleman Corners, meant we were coming back to a place that our hearts call home.

21 comments

21 comments

Comments (21)