My father, who was born in Indiana in 1886, once told me how exciting it was when the traveling circus arrived in his small town around dawn on the local train. Its imminent arrival had roused the inhabitants of Muncie to watch it unload people of all shapes and sizes, fierce animals in cages, tame animals on leads, small tents for the humans to occupy as sleeping quarters, and the makings of a very large tent. After a slightly disorderly parade through town, followed by all but the very oldest inhabitants, the workers set about putting everything in the right place for the much-anticipated show.

A generation later, my experience with a circus was very different. Our family lived in a suburb of New York City, and once a year my father took my younger sister and me to the circus inside Madison Square Garden. I probably was not even aware that circuses were traditionally held outdoors in huge tents. It was a magnificent spectacle nevertheless, but the most vivid memory I have of it was the “freak show” on the floor below the main show rings. In a cage there was a huge mountain gorilla named Gargantua who gave me nightmares for weeks afterward. And the strange people on exhibit frightened me.

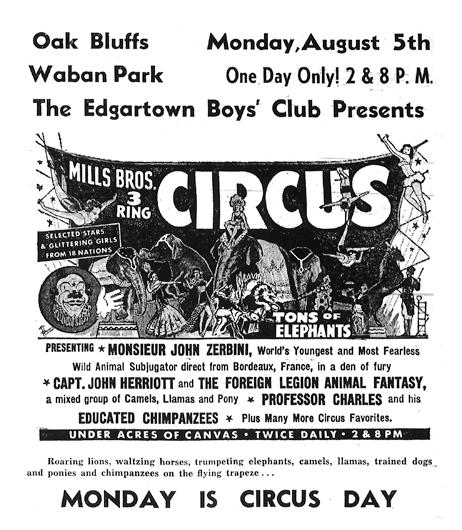

In 1963, when I had three young children, had been married for sixteen years, and lived on an island, I doubted my children would ever experience some of the city events I had been privy to. But then, while reading the April 26, 1963, issue of the Vineyard Gazette, I noticed with astonished joy that the Mills Brothers Three Ring Circus would perform on Martha’s Vineyard in August. In the early 1960s the Mills Brothers circus was one of the largest three-ring tent shows in the United States, and the first ever to play on Martha’s Vineyard. It was to be, the Gazette reported in a later article, “the biggest over-water movement of animals since Noah coaxed a balky donkey up the gangplank.”

The spectacle was co-sponsored by the Edgartown Boys’ Club and the Harborside Inn, but the person most responsible for bringing the show to the Island was Cliff Lenox, a booking agent and an Oak Bluffs summer visitor. He had seen a film about the Mills Brothers circus, and after a late-night discussion, the advance agent made a 2 a.m. phone call to Jack Mills, one of the three brothers who owned the circus, to pitch the outlandish idea. Lenox’s grandparents had a summer home on Waban Park, and he had spent many summers there. His great-grandfather was an early member of the Methodist Camp Meeting Association. His grandfather Fred Newell owned one of the first automobiles on the Vineyard, but was not allowed to drive it while the Sunday services were going on in the Camp Ground. He knew the Island well and believed he could make the circus happen. Eventually, Mills said they would come, but only if Lenox would make all of the arrangements.

It took months of figuring out how to get the circus across Vineyard Sound. There were nearly eighty-five trucks, cars, and trailers, not to mention cooks, clowns, trapeze artists, animal trainers with all their animals, and everyone involved in the care and safety of all the people and animals. But on the night of Saturday, August 3, 1963, the circus made its way down to the ferry landing in Woods Hole, where the Islander and Nantucket were waiting to make multiple crossings through the night.

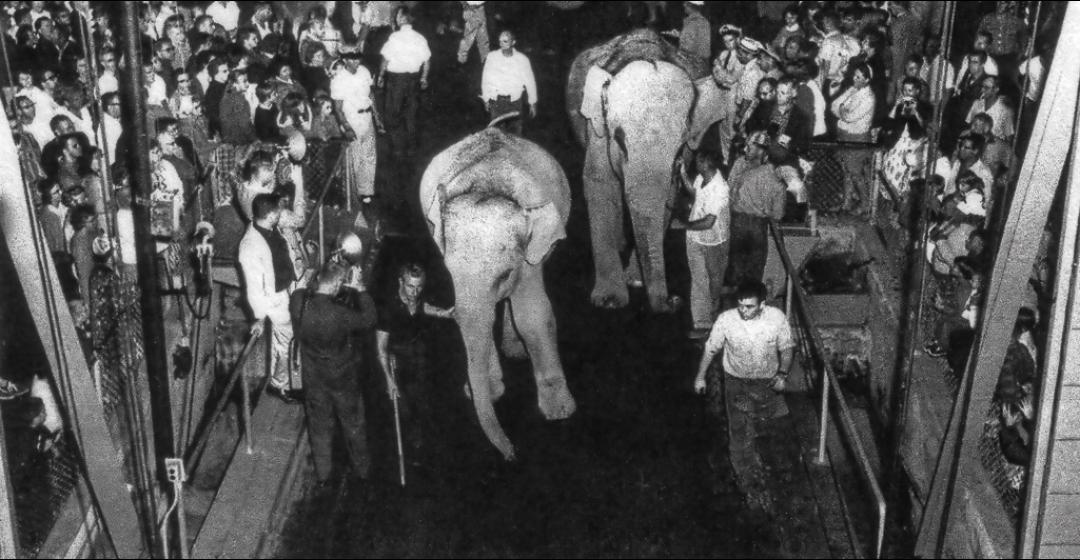

This was such an unusual event that eleven television studios and press syndicates had sent crews to Woods Hole to record the loading process, and by midnight there were many photographers and journalists gathered on the dock to record the animals marching on to the ferry.

According to Lenox, several thousand residents of Cape Cod also gathered in Woods Hole that night to watch the spectacle. To please the crowds, roughly twenty animals were unloaded from their trucks to walk – some of them two-by-two – aboard the Nantucket, which by then was being called Noah’s Ark.

While the animals were walking aboard, someone in the crowd set off a package of Chinese firecrackers that created a few moments of panic as the horses and camels reared up and pulled at the straps that were held by their handlers. Meanwhile, on the dock, five elephants

put on a small show for the crowd.

Among the many animals arriving in Woods Hole in the dark of night was “Miss Burma – the world’s most famous performing elephant.” She was carried in a big white trailer that proclaimed her title in large letters along the side. According to Lenox, Miss Burma had marched in President Eisenhower’s inaugural parade. The visit to the Vineyard coincided with Miss Burma’s birthday, so on Sunday, the day before the performances, she was

honored on the outside deck of the Harborside Inn. Although she spurned the large sugary cake that had been made for her, it was enjoyed by her human attendants and some of the hotel employees.

It was the middle of the night when the circus arrived in Vineyard Haven, but several hundred Vineyard residents were there to greet it. The first ferry was filled with the cook tent and all its workers and supplies, so that they could set up eating facilities and be ready to serve Sunday breakfast in Waban Park for the later arrivals. Several hours later came the Nantucket carrying nineteen large tractor-trailers, three regular trucks, and fourteen horse trailers along with the cars that pulled them. Squeezed in among all these huge vehicles were about a dozen passenger cars.

From Vineyard Haven they had to wend their way to Oak Bluffs, and at least one of the circus vans mistakenly ended up in Edgartown. At about 3 a.m. Sunday morning, residents on Morse Street were awakened by elephant noises, lion roars, and human voices. “Is this Oak Bluffs?” one voice asked. Finally, some policemen arrived to point them in the right direction.

Back then, Sundays were a day of rest, even for the circus, and the two performances took place on Monday, August 5 – one in the afternoon and one in the evening. Oak Bluffs was inundated with people and cars, many from Cape Cod and Nantucket. It took the Oak Bluffs and Edgartown police as well as the sheriff and his deputies to keep them in order and moving along.

The afternoon performance had a few empty seats, probably because so many children were seated on the laps of their parents. But that night all 3,000 seats were sold out by the time the opening procession began. As they had in the afternoon, the hoofed animals – horses, camels, llamas, and ponies, as well as the lumbering elephants, portrayed The Arabian Nights, Old King Cole, The Owl and the Pussy Cat, among other familiar stories. The elephants performed their ballet; the lions behaved under the watch of the dashing young tamer, John Zerbini; the acrobats again flew through the air without a misstep. The clowns, meanwhile, kept the crowds laughing as the audience drew in their collective breath with fear and excitement. Before they had had enough, the music crashed to a halt and then played softly as the tent emptied into the summer night.

But even while the huge audience was enjoying the final performance, the mostly invisible circus crew had struck the smaller tents and loaded the trucks for their departure. The elephants had been given their daily allotment of 250 gallons of water apiece. The ferries were ready and waiting. No one was wasting time; they were headed for a performance on the Cape on Tuesday.