For most people of note, a visit to Wikipedia helps clarify some points and makes the narrative a bit more clear. But when trying to get a handle on David Weagle, forty-one, and his patented DW-link, a suspension system he invented in the late 1990s for mountain bikes, the problems only intensify. Phrases like Euler’s second law, which focuses on the rate of change of angular momentum about a fixed point, begin to make the head go cloudy. Compression damping doesn’t help, nor does anti-squat suspension.

One thing is clear, though. The downhill mountain biking world is divided into BW and AW – Before Weagle and After Weagle. Since 2005, professional riders using his suspension system have dominated the world downhill championships, the pinnacle of this sport. He holds numerous patents, and bike companies so advanced you haven’t even heard of them carry his equipment. Pros drop at least $10,000 for one of his bikes.

How did this happen, a relatively mellow guy living in Edgartown becoming the most important engineer in the mountain biking community? The short answer is Weagle went searching for the Holy Grail of bike mechanics and when he didn’t find it he invented it himself.

Weagle’s workshop is in a large barn, off a no-named dirt road near Morning Glory Farm. Some dudes create man caves in their basements, usually dedicated to the religion of comfort and ease, with large-screen televisions, fluffy couches, and the old recliner with the stuffing coming out the sides that the wife said to get rid of or banished from the living room. There’s a bar somewhere, too, and at least one refrigerator.

Weagle’s man cave is more like a bat cave, a place where serious work is done amidst old cars, motorcycles, scraps of metal, tools, and, of course, mountain bikes of all shapes and sizes (no road bikes, not here, not ever). To call Weagle Batman is not the right metaphor, though. He’s more like James Bond and Q rolled into one – the inventor brain and the courage to use the prototype out in the field.

Weagle is a mechanical engineer by trade and if you close your eyes when he talks to you, that is exactly what he seems to be. A very brainy fellow who enjoys spending time with numbers, sometimes crunching data for days with no regard for sleep in order to perfect design flaws. When you open your eyes, though, you see a scrappy guy who looks like he just finished a serious skateboard session, or smashing the drums in a punk rock band. More likely he just returned from testing a new bike out on the trails of Martha’s Vineyard, or on some more serious hills in New Hampshire.

Weagle grew up in Rutland, Massachusetts, but moved here after he met and married Linley Dolby, an Islander. He went to Wentworth Institute of Technology in Boston, majored in mechanical engineering, and had his heart set on creating Formula One race cars. In school he began to focus on a competition called the Mini Baja, where students around the country compete to make the best small off-road race car.

“It was an elective but I basically made it my major,” he said. “I tailored my entire schooling, everything I did. I concentrated on that.”

In other words, he majored in creating a souped-up golf cart with off-road suspension and knobby tires that could hit speeds of 100 miles per hour on wild terrain. A golf cart with roll bars.

Weagle and his team of fellow students did well at the competitions, but more important, that was where he cut his teeth on suspension design and working with carbon fiber, the material from which all top bikes today are created. Carbon fiber is used extensively in the aircraft industry, both military and commercial.

Appropriately enough, after college he went to work for the U.S. Department of Defense in Boston, helping to develop vehicles for Special Forces operations. “Payload delivery vehicles for clandestine operations” is how he described the work. “Could be anything. Lot of times we didn’t even know what the payload was.”

He wasn’t thinking about a future in the bicycle industry. He was focused instead on learning about the functionality of these military machines, working with great minds – former engineers from the Apollo moon missions – and picking their brains every day. At first this was focused on his day job, how to make the suspension of these Army cars work at their peak. But gradually, as he began participating in downhill mountain biking on weekends, he began to get curious about what makes a really good bike. The difference between him and countless other cycling enthusiasts who get deeply interested in the machinery is that he knew what makes rubber meet the road, and what makes it leave it too.

After talking to experts in the field of mountain biking, reading magazines and books, and checking out marketing plans that promised things he knew a bike couldn’t deliver, he decided that no one really knew what they were talking about. Or in his words: “I’m looking at it and I’m saying, ‘I don’t know a lot about kinematics, but I know that linkage cannot make straight-line motion.’ This is one of the best companies in the world, supposedly the pinnacle of technology, and they have no clue what they are building.”

In plain English this means Weagle was focused on the rear suspension unit, the shocks and linkages in that part of the bike that make it essentially go forward. Each moment in that line can either help or hurt a rider, and the more he studied what was already out there, he realized no one had yet broken down the chain of command for every single movement along the bike power structure. So he did it himself, dedicating years to the process, and as a result became the guy – not just an important guy, but the guy – who knew more about the mechanics of two-wheel design than anyone else ever had. That’s a big pill to swallow.

“For at least a year I didn’t even believe it,” he said. “That’s why I spent so much time talking to my coworkers. Maybe it’s because I’m not the most intelligent person in the room and I need to understand, and in order to understand something I need to break it down. Or maybe it’s because I continually believe I don’t understand, and some people look at something and say, ‘Oh I get it.’ I challenge myself and challenge the status quo. When you stop learning you stop being relevant. Like Tom Brady says, ‘You’re either getting better or [you’re] getting worse.’”

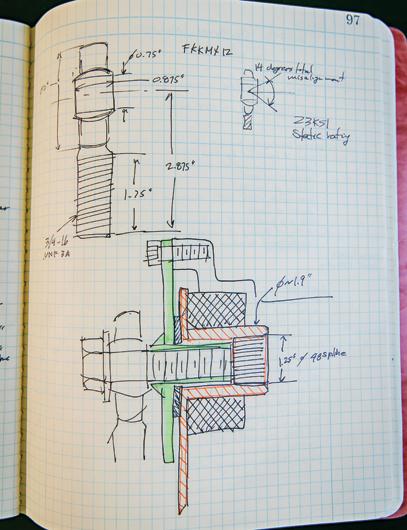

But after all that understanding comes the task of putting it into practice by building a prototype.

“I wrote a list of parameters: What do I want to achieve fifteen years from now, twenty years from now, 100 years from now, and what makes a performance motorcycle or bike? And now I had to develop and synthesize a linkage system to achieve these goals.”

While still holding down his day job. The military needs its vehicles, after all.

He started by using two short links connected to a large triangulated suspension. Then, by manipulating the lengths of these links, he checked how they performed under breaking and accelerating and how the shock was compressed, and about a hundred more variables that could affect a ride.

“All those things separately can have a massive effect on how the suspension feels and how you interact with the bike,” he said. But Weagle wasn’t looking at each part in isolation, what engineers had been doing for so long. His was a holistic system, and when it was finally created he went with some riding buddies to see if it could conquer Vietnam, a legendary hill near Milford, Massachusetts.

“It was the first ride of the year; it was early in the spring. It was a big untamable hill that we all tried to climb,” he remembered. “I was by far not the strongest climber and I crushed that hill and all my buddies were in the weeds. I got off the bike and just looked at it. It was so much better than I expected.”

But there still wasn’t a name for what he created, so a friend dubbed it “the DW Link” and it stuck. In the end, Weagle licensed the product to a company and it was time to quit his day job.

Part of the rest of this story involves a young inventor from the outside discovering that big business doesn’t always play fair. Weagle has had his legal battles with some of the big companies, and there have been plenty of knockoffs created in the industry. But he doesn’t like to dwell on those issues. He’s too busy consulting on design projects, working on new inventions, and licensing older ones. Plus, he’d much rather give a tour of his barn laboratory and talk about the latest big thing in mountain biking: fat bikes with huge tires originally made for desert and snow biking, but now forging a path in the traditional mountain biking community. He points to the first full-suspension fat bike “in the world” leaning up against the wall – which he built, naturally.

He’s also thinking about taking a ride. The Vineyard is a difficult place to live, because he has to travel to Asia so often. (That’s where everything in the industry is built.) But there are good trails to ride here, he said.

“We have hundreds of miles of good cross-country trails. I don’t know the names; I make the names up so we can communicate where to meet. And probably ten different people call them ten different things. West Tisbury is pretty great, so is Chilmark. The hillier stuff is always the better.”

And it’s this getting out in the woods that keeps him going, crunching more data, and figuring out how to make a better bicycle. True, his high-end carbon fiber bikes are out of range for the average consumer, but you can still get a solid mountain bike, with full suspension, for $600 to $800. And then all you need is a helmet to hit the dirt. This feels a lot better to him than the old days of working for the Department of Defense.

“It all comes down to, I kind of looked at it and it wasn’t making people’s lives better. Originally it was, when we were doing stuff for explosive ordnance disposal, but I saw a vehicle that I had worked on, on like CBS news, with a gun on it and it just hit me that I didn’t like it. I didn’t feel good about it. Now I go out and meet a guy who was out of shape who says ‘I’m going to be there for my kids now.’ That’s what it’s all about.”

4 comments

4 comments

Comments (4)