Three years ago Janice Frame, the artist and former art teacher at both the West Tisbury School and the Martha’s Vineyard Regional High School, picked up drawing materials, scissors, colored and metallic papers, and began creating again. The new spurt of creativity came after a five-year-long “dry spell.”

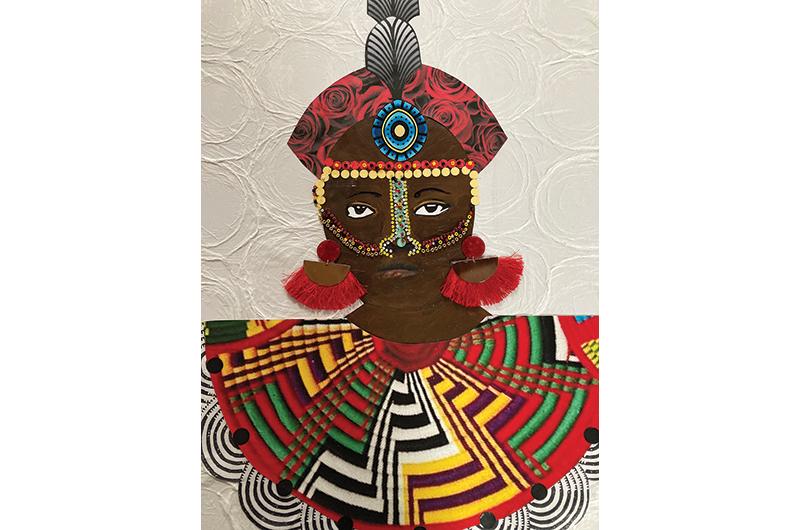

For more than a decade, while teaching, her work had focused on creating three-dimensional dolls she called Reddancers, based in the traditions and heritage of African tribes. Though Frame has long held a strong sense of African American identity, the dolls were originally inspired by the books of photographers Carol Beckwith and Angela Fisher.

“Those two women have captured the beauty of African people: the ceremonies and the colors that adorn the people,” Frame explains. “I was just immersed in it. I kept saying, ‘I have to do something with these things. I have to make these people and their beauty live.’”

Her focus on African identity grew as she thought about how different cultures have different faces. “They have their own regalia. Their sense of all that color,” she says. She conducted extensive research and commissioned authentic pieces, such as hand baskets, ordering miniatures from Africa to adorn her dolls. “We’ll put red, then we’ll put blue and green, all in the same place. That sense of pattern. The beauty of body adornment – the jewelry and basketry – always fascinated me. That’s what the dolls came out of. I really truly loved those dolls and tried to make them as authentic as possible.”

Frame eventually built upon the idea of the Reddancers when she began creating dolls that were inspired by the stories of the enslaved people who lived in the coastal South of the United States, particularly her own place of origin, South Carolina. She describes some of the dolls created during this phase as “very Daughters of the Dust.” They were shown and sold at Cousen Rose Gallery in Oak Bluffs for many summers, and were displayed at historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs), including Howard University in Washington, D.C., and Wilberforce University in Ohio. Bill and Hillary Clinton accepted two of them as gifts from the artist. Then, as Frame describes it, the dolls simply “left her.”

She didn’t know what form her work would take and wasn’t finding inspiration. “I was dead for about five years. I didn’t do anything,” she says. “I was probably tired. And I was longing for my teaching job.”

She was aided by support from her friends, particularly author and fellow educator Lynn Ditchfield, who recently featured Frame’s work in her self-published book Borders to Bridges: Arts-Based Curriculum for Social Justice.

“Lynn told me what I was actually going through was grieving. She said, ‘Janice, don’t push anything. Just wait and be still for a while. Your direction will come.’

“I said, ‘Lynn, this is year three!’

“She said, ‘It doesn’t matter. Just relax and it’ll come to you.’”

In some ways, Frame was probably born to be an art teacher: she comes from five generations of educators. Early on in a family teaching moment, her mother posed to young Frame, her siblings, and her cousins the philosophical question of “what is beauty?” She asked it at the family dinner table, while the children colored with crayons, or played with paper dolls on a South Carolina front porch.

“When I was growing up, we had art everywhere,” she recalls. “I learned to look at a piece of artwork not as a picture but as an expression. That was the karma around the house.”

She also felt the influence of her great-uncle Fetaque Sanders, a magician and puppeteer who created unique vaudeville-era marionettes that sparked his young niece’s imagination.

Most important, perhaps, she was surrounded by support to choose her own path. Growing up in an African American family in Columbia, South Carolina, her relatives were accomplished in the fields of medicine and business, including doctors who founded one of the South’s first Black hospitals. “My mother’s family was very middle or upper-middle class,” she says. “I never had any of the African American stereotype of coming from a hard life.”

Like many other relatively prosperous Black families of the time, Frame had early connections to the Vineyard, and her Island roots are intertwined with her creative identity. As a child, she summered with family members from Philadelphia who owned property on Daggett Avenue in Vineyard Haven. She remembers the area being “all woods.” She, her siblings, and cousins went to the beach and the Flying Horses. “We just had fun,” she says with a shrug. “We did what Island people do.”

Her mother sometimes took the children to Gay Head (now Aquinnah) for long days at the beach, and Frame now laughs at the memory of how long the car ride up-Island felt. At the end of that ride would be glorious beach days. In particular, she recalls a long slide that started at the top of a cliff, which people would slide down all the way into the ocean.

But even on those playful summer days, she was making art. “I was fascinated by the clay,” Frame says. “Every day I made all these little pots. I would hide them in the dunes or between the rocks. Everyone else was out there swimming and I was by myself, making these little clay pots. They would eventually wash away.

“The thing that tricked me into loving the Vineyard so hard was the openness to art,” she explains. “It had that atmosphere and just breathed art to me. I loved the way the Island supported artists. I loved to go to the [Art] Workers Guild. It was a place where artists worked and downstairs was a gallery. You could touch and feel the art being made.”

In 1955 Frame’s family relocated to Cincinnati, Ohio, where her parents were outspoken members of the civil rights movement and struggled against racial discrimination. Unlike in Cincinnati, Frame remembers race not really mattering on the Vineyard in the summer. “I don’t think I ever thought about the race issue here and the fact that we were part of a Black family coming here,” she recalls with a mix of pride and wistfulness. “We played with everybody.”

Those happy memories played a role in her eventual return to the Island. After earning her undergraduate degree in fiber and textiles as well as art education at Fisk University, a Nashville HBCU, she married classmate Leo Frame. Next came a stint in Massachusetts, where he pursued a master’s degree at the University of Massachusetts. Then the couple took teaching jobs in Atlanta, where they lived for eighteen years and had two sons.

They had a good life in Atlanta, and they might have stayed. But the disappearance and murder of young Black boys in that city in the late 1970s and early 1980s made them fear for their sons’ safety. When Frame was offered the position of art teacher at the West Tisbury School in 1985, she grasped the opportunity to leave the city and relocate to the Island. She, Leo, and their sons rented year-round in West Tisbury before purchasing their Edgartown house, where she and Leo continue to live. The lower level serves as her art studio and his workshop. Soon after, she earned her master’s degree in curriculum and instruction.

In 2000 Frame moved over to the Martha’s Vineyard Regional High School, furthering her connection with students. Today, the walls of the Frame home are adorned, gallery-style, with artwork created by the young artists nurtured during her tenure. She cites notable artists, including Kara Taylor, Max Decker, Dan VanLandingham, and Kenneth Vincent, among the many former students she continues to see and of whom she is proud. Just a couple of years ago, Frame and Taylor ran into each other after years of not being in touch, and Taylor joyfully related what she had learned from Frame in first grade: to love your colors.

But as excited as she is about the students who pursued art professionally, Frame says she takes equal joy in those to whose lives she brought beauty. She recalls one young student at the West Tisbury School who proclaimed, “Every time I come into this room, my heart leaps.” The expression and the memory of it is one Frame holds deep in her heart. “To this day, it’s the most important comment of my whole life,” she says.

“Teaching was my love,” Frame says wistfully. “That was a joy. I still miss it to this day. I’ve been retired since 2013 but I would go back tomorrow. If I could, I would go back and teach on Monday.

“Everyone is an artist,” she adds. “Everyone has that potential, whether they are creating or not.”

It was likely her faith in the enduring nature of artistic potential, honed over so many years of helping young artists, that saw Frame through the period after the dolls that had defined her art for so long took their leave. She was frustrated, perhaps, but never in despair about the fallow period, she says.

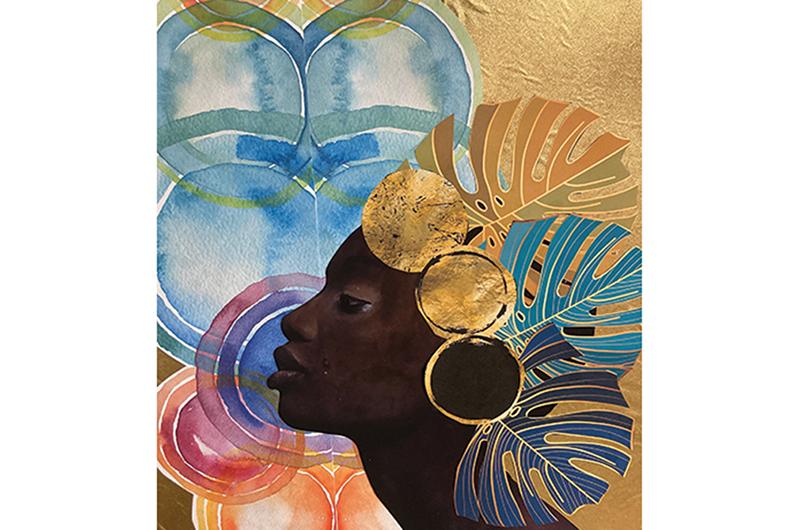

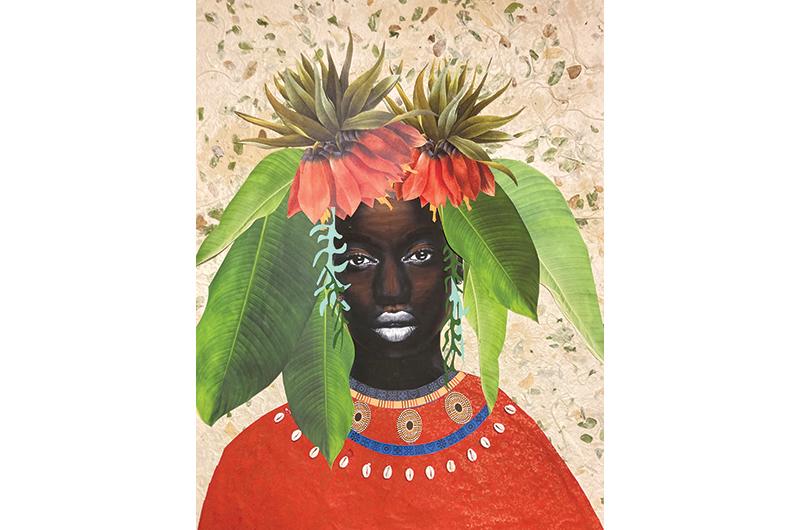

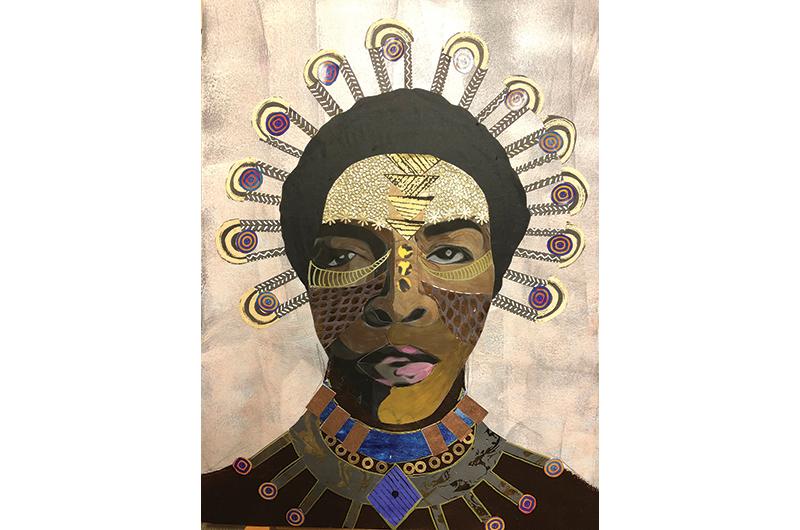

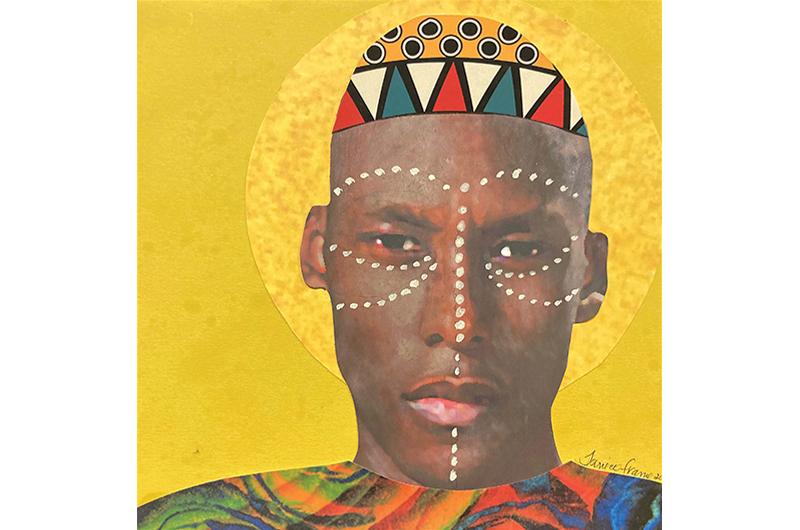

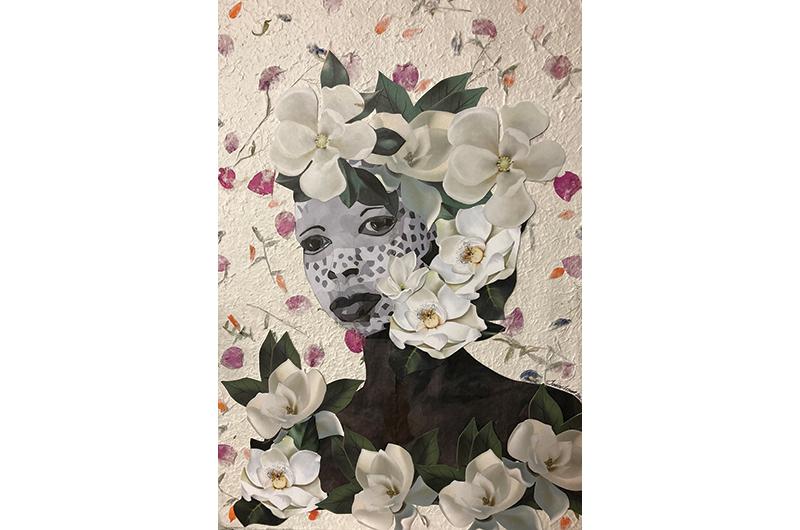

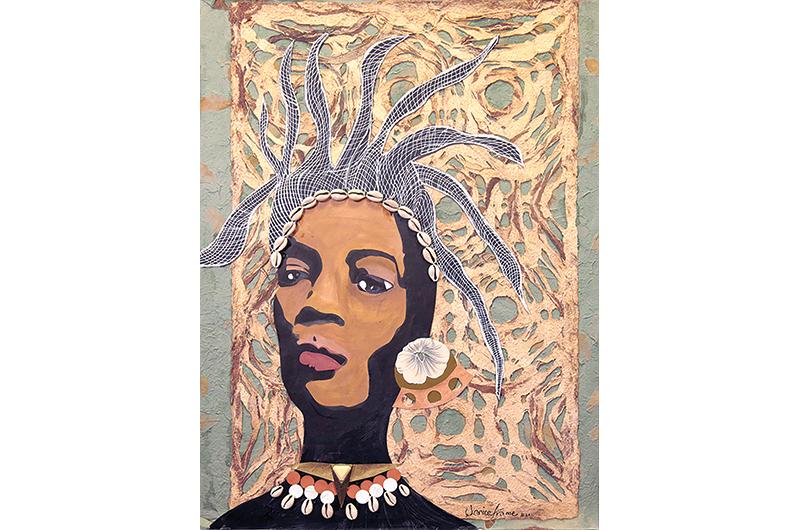

Then, around the start of the pandemic, she began discovering a new creative life. It was populated with new shapes, faces, and characters, which she began presenting as large-scale, mixed media portraits. An African girl with shoulder-length dreadlocks gazes with determination from underneath a headpiece of leaves and flowers. Against a golden background, a woman elongates her arms toward the sky to hold in place a brightly colored woven basket that tilts as she carries it overhead, performing a morning ritual while adorned in metal jewelry on her neck, shirt, and skirt. Three wise faces – partly covered with white tribal paint and each wearing elaborate head coverings of twigs, flowers, or fruit – stare out from the canvas with looks of surety, knowledge, and perhaps a bit of defiance.

In this latest chapter, Frame had come back to the familiar topic of African identity but found her exploration taking new form and with new images. Though inspired by heritage, Frame says she is not true to any particular tribe. She feels empowered by artistic license to create her own images built around African faces, vibrant colors, body silhouettes, and items.

She approaches each mixed-media piece as a portrait, starting with an African face found on a clip art site and arranging it in relation to patterns and objects or people, set against rich, bright colors. In her home studio are bins of fabrics, papers, shells, jewelry, and cut paper. With crayons and markers, she enhances the cut-out faces with illustrated hairpieces, plants, or abstract shapes. Frequently, she uses a style called contour drawing, which is one continuous line. She works with acrylic paint on plywood purchased at E.C. Cottle, an Edgartown lumberyard, and applies a resin finish.

“Most of the pieces that I’ve done…I’m so attached to them as figures, as people, that I have conversations with them. I’ll say, ‘Well now, what do you think? Do you need another earring? No, that earring doesn’t work. Let’s try this one: try a gold one.’ I have these emotional conversations that come from a heart space versus a head space.

“They’re my people,” she says with a shrug. “They’re my friends.”

These days, a lot of these “friends” can be found on North Water Street in Edgartown at the Eisenhauer Gallery. On Facebook, Frame’s portrait work caught the attention of Amy Cash, the gallery’s assistant director. Gallery founder Elizabeth Eisenhauer was also intrigued by the work and asked Frame if she’d be interested in exhibiting with her. The artist’s first instinct was uncertainty about whether work inspired by “the deep, deep soul of Africa” belonged in an Edgartown gallery. “But Elizabeth took the chance,” Frame says. “She took a big, big risk.”

Within two to three days, the works had sold. “I couldn’t believe it,” she says with a shake of her head. “I didn’t think I would be successful.”

Since then, Frame has continued to expand the range of her work in detail, scope, and size; one recent piece measured forty-eight by forty-eight inches and had to be carried by two people. Eisenhauer has encouraged her to create such larger pieces. As summer 2023 approached, Frame’s studio space showed works in progress: contemplative faces arranged against brightly colored backgrounds, frames awaiting finishing, and a few lacquered pieces watching over the artist as she worked.

Her notebook is full of questions about what it means to be African, reflections on African people, the love she has for humanity, and a joyful mission statement: “I have chosen joy in culture. Culture matters.”

She continues to explore and find beauty in physical places, too, including Atlanta, where she and Leo now snowbird for a few months each winter so that they can spend time with their grandchildren. But they always return to the Island. “The Vineyard is my love. It’s my home. It’s where I am, where I work. It’s where I do. I have been embraced. I have been loved. I have been cared for by that community.

“I’ve just been happy,” she says contentedly. “With all that support and affirmation, who wouldn’t be?”

3 comments

3 comments

Comments (3)