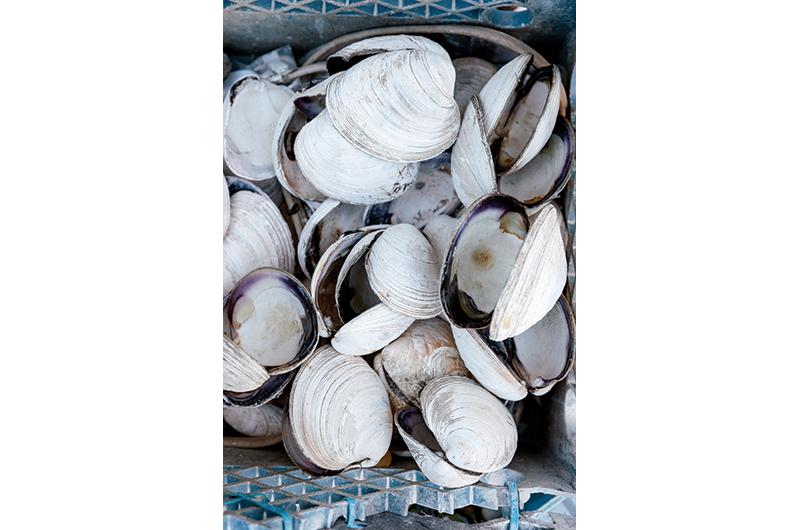

Wampum: despite the popularity of the deep purple variety, it is a word in the Wôpanâak language that translates literally to mean “white shell bead.” In the Wampanoag tradition these beads are the treasured gift of the quahaug, both the tribe and the hard-shell clam having thrived on the island of Noepe for thousands of years.

“They are part of our circle of life,” said Donald Widdiss, an Aquinnah Wampanoag who appreciates the quahaug as both sustenance and the subject of his artistry, “and we are part of that circle of life, not the apex.”

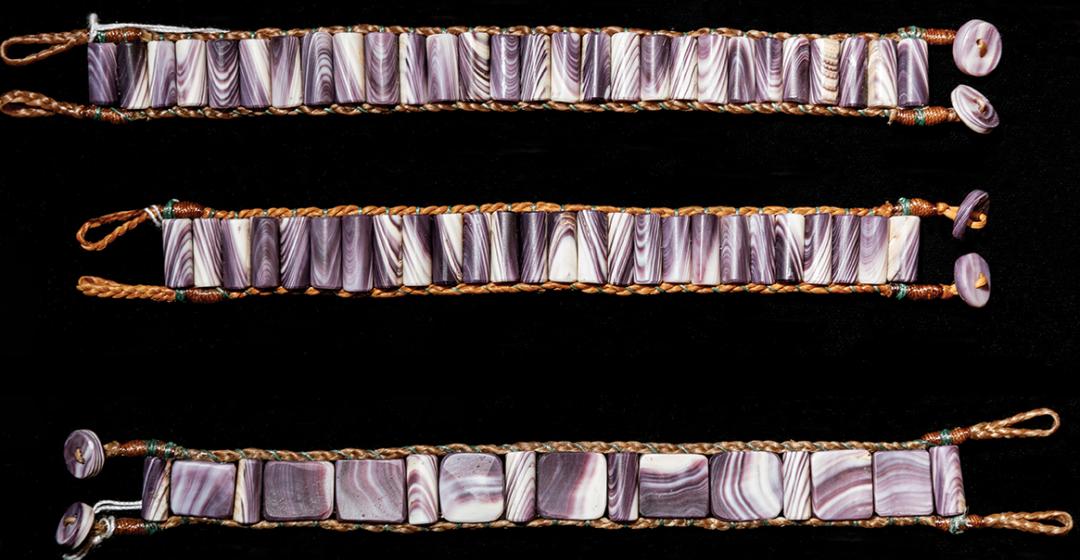

His regard for the quahaug, whether in the form of a bracelet or in a bowl of chowder, is the same, he said, rubbing his fingers over a row of wampum council beads wrapped around his wrist. He explained how his consciousness is imbued in his work, as is the spirit of the quahaug sacrificed for each bead. “It’s a living thing. You wear this, and you are gonna have dreams you can’t explain.”

There is nothing fancy about a quahaug on the outside; only the uniform ridges that indicate growth distinguish it from a rock. The appeal is found on the inside, once the meat is removed and its slick, mostly pearly white surface with gradations of color from lighter to deep purple emerging from the hinge is revealed. A shucked shell might serve as an ashtray or a soap dish, while broken chips washed smooth in the surf

are keepsakes of a summer day.

Prior to European contact in the seventeenth century, wampum adornments were made from chunks of the shell that had been smoothed, shaped, and drilled using stone and bone tools. With the introduction of goods arriving aboard European trade ships, the crafting of wampum became more sophisticated. Metal nails were used to drill the smaller tube beads that have come to be known as council beads. Those beads were prominent in elaborate ornamental jewelry and belts held by tribal leaders of high rank and socially important tribal members. The seventeenth-century colonist and historian Daniel Gookin compared the appeal to English treasures: “It answers all occasions with them, as gold and silver doth with us.”

Most prevalent of the makers of wampum were coastal tribes including the Wampanoag, Narragansett, and Pequot, but the use of the beads in the making of belts displaying hieroglyphic tribal history – or, in some cases, messages of diplomacy woven into the design – spread deeper to inland territories. One of the most famous of those weavings is the Two Row Wampum Treaty belt, which is made up of primarily white beads with two rows of purple ones. It symbolically established Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) sovereignty in their relations with the Dutch in 1613.

“Wampum was important because the original intent was to show status and respect,” said Widdiss. “The two-row belt was very simple: to show the Dutch they can live in parallel, but they don’t cross.”

The English and Dutch recognized the significance of wampum early in the 1600s. By the 1630s they had began using it as currency, making wampum the earliest form of legal tender in the colonies.

Today, Widdiss has made a name for himself creating bracelets modeled from his knowledge of seventeenth-century council beads. The historic connection to the wampum tradition is so important to him that at one time he made a bead using primitive tools, including a pump drill and a nail. “It took me thirty hours,” he said, leaving him unapologetic about using modern power tools to do his work now.

Still, even with modern tools, it is hard and tedious work to grind and shape beads and make pendants, the latter which he sells for anywhere from $150 to $400. Widdiss begins by digging for quahaugs at Menemsha Pond. Using pliers or a hammer, he breaks off the colorful areas of the shell and uses a jeweler’s saw to make a rough cut of the bead. He refines the shape using a grinder, then buffs it on a polishing wheel. Proper protective gear is required; dust from the shells is harmful if inhaled. The shells are delicate, and breakage is common.

Finally, he drills a hole through each bead and weaves them together.

As jewelry, wampum has been trending in popularity on Martha’s Vineyard for the last several decades. It is worn as bracelets, earrings, and necklaces by everyone from farmers and fishermen to celebrities and the affluent. To some, it has become emblematic of Island culture.

To meet the demand, more than a dozen artisans on the Island presently create some form of jewelry that features the purple and white shell cut, carved, and tooled. Some Island gift shops stock mass-produced pieces. But arguably the most authentic wampum is created by those Native artisans who have a unique cultural connection with the quahaug. Wampum is to northeastern Indigenous jewelry as turquoise is to Native jewelry of the southwest. Topping the list of the most recognized Aquinnah wampum jewelry makers are Berta Welch and Widdiss.

“Our ancestors have been here for more than 12,000 years,” said Welch, “and so has the quahaug. We have a special affinity with it.”

This is not to say that “authentic” wampum made by Wampanoag artists necessarily looks any particular way. Of the Island’s Wampanoag artisans making wampum jewelry, Widdiss and Welch have risen to esteem and popularity not just with their work, but with dramatically different intents, methods, and styles. While Widdiss’s pieces tend toward the more traditional, Welch’s work is distinctly contemporary.

The modern convenience of power tools is not lost on Welch, who stood amid buckets of shells in the workshop attached to her Aquinnah home. On the work bench chunks and chips of shell lay in different phases of production; she doesn’t know what form they will take until she is finished.

“My work has refined the natural process: cutting, grinding, and shaping shell with modern tools,” she said. “As the dust falls away, I continue to be amazed and thrilled by the unknown design that emerges. Each one is different. How can you not be motivated to know what will come next?”

Welch’s work features a mosaic of wampum inlay often including bits of other natural substances, such as turquoise, apple coral, and mother-of-pearl framed in sterling silver. It has been on display in numerous exhibits and museums, including the National Museum of the American Indian in the nation’s capital. As the architects of the museum were creating the design, elements authentic to the diversity of Indigenous culture was the highest priority. In an effort to represent the northeast, they drew inspiration from Welch’s work and commissioned her to create an inlay décor that is now on permanent display in the museum’s Chesapeake and Roanoke gift shops.

Welch credits both of her parents for encouraging her to follow her artistic instincts. Her mother, Bertha Vanderhoop, made pottery with clay she collected from the Gay Head Cliffs. Her father, Jose Giles, was a silversmith plucked from the silver mines in Taxco, Mexico, and schooled by the twentieth century master William Spratling. The rare and beautiful work of her parents are treasured family heirlooms.

“Being raised in such a culturally artistic environment inspired me to see the resources around me in a very creative way,” she said. “While other children built sand castles on the beach, I was finding treasures in the sand. Each chip of surf-washed wampum exposed nature’s own hand creating individual beauty.”

When she isn’t grinding shells into art, Welch often can be found behind the counter at Stony Creek Gifts, a shop on the Gay Head Cliffs that has been operated by her family for eighty-five years. Among the seasonal items and gifts, her jewelry is on display at prices ranging from $75 to $300.

Widdiss was similarly inspired by his mother, Gladys, who also sold sun-dried pinch pots on the Gay Head Cliffs as a young woman. “She would give us old pillowcases and send us down under the cliffs to collect the different colors of clay,” he recalled. During the school year they lived in Wayland, Massachusetts, but their Island home in Gay Head (now Aquinnah) was where they thrived. Having to haul clay was a small price to pay to be in the place they considered home. The clay produced a treasure for tourists who wanted to take home a piece of the Island. Today, Widdiss provides a treasure in the form of wampum jewelry.

He sells his pieces at the Great Put On in Edgartown, the Granary Gallery in West Tisbury, the Copperworks in Chilmark, and the Wampanoag Trading Post & Gallery in Mashpee, Massachusetts. He also works directly with many clients, some of them high profile, with whom he has a personal connection. Often these customers come to him with commission requests.

In recent years, there has been a call to further define the term of wampum jewelry as that created exclusively by Indigenous people. Non-Native crafters have rebranded their products as shell, ocean, or quahaug jewelry. Widdiss draws another distinction.

It is something he is a purist about. The bits of quahaug shell found on the beach are not wampum, he said. Nor are the hearts and hooks and other shapes he makes into pendants. “That’s just quahaug shell jewelry.” While only the tube beads are considered true wampum, his pendants dangling from hand-crafted sinew rope and intricately wrapped are very popular.

“The beads are intended to evoke a response, developing an understanding of how Native American bead makers and artisans might impart traditional values through this culturally significant craft,” he said. “Without this understanding the beads have no value, meaningless in their context and execution.”

Welch doesn’t disagree with Widdiss’s characterization of true wampum, but that won’t change the common nomenclature for the work they do. “Really none of the work we do with modern tools can be considered wampum in the truest sense,” she said. “But we have evolved from hunters and fishermen who lived exclusively off the land to people who coexist and compete with our colonizers. We are survivors and our art has evolved with us.”