In 1976, Richard Lee, an artist, dancer, and world traveler who had recently arrived on Martha’s Vineyard, embarked upon a new profession: restaurateur. Island friends had purchased the home between Alley’s General Store and the First Congregational Church of West Tisbury, which had been the site of a tea room where refined ladies gathered to lunch. Because the owners were in danger of losing the right to purvey food if they didn’t continue to operate a restaurant, Lee was asked to step in rent-free for a year. Thus, Richard’s Dessert Gallerie was born.

Lee, who had considerable experience as a charming host, hired pie and cake bakers and a chef and launched into the project with his characteristic humor and enthusiasm. The environment he created was that of a genteel New England establishment, with the exception of his own reverse glass paintings, which he hung on the walls.

On opening day, Lee, a spritely man with a lilting voice and a dancer’s gait, greeted and welcomed his guests. The patrons took their seats and gazed sedately at their largely familiar surroundings. On the menu were fabulous desserts and, as his friend Sally Hamilton remembers, “The best lamb chops I ever ate.” As the tea ladies took in the room, their eyes alighted upon whichever strange, shockingly colored painting was nearest, which caused a momentary flutter. But when one of the women at the table went to the bathroom and returned, pandemonium ensued. Lee had (somewhat discreetly) put what many would call pornographic, but might more accurately be labeled pagan, paintings in the bathroom.

There was a walk-out or two, and some never returned after their first visit. Of course, many, like myself, responded positively. The happening that was the Dessert Gallerie lasted just a brief moment in time but lives on in Island lore. It is the root of Lee’s fame and notoriety on Martha’s Vineyard.

For the next thirty-six years, Lee, who died in 2012 and is the subject of a retrospective at the Martha’s Vineyard Museum in Vineyard Haven this month, would go on to entertain and sometimes shock the Island with his vivid work. But let’s not give too much weight to the sexual aspect of his paintings. The reality is that even his nonsexual images were startling in their colorful presentation of an inner imagination that knew no bounds.

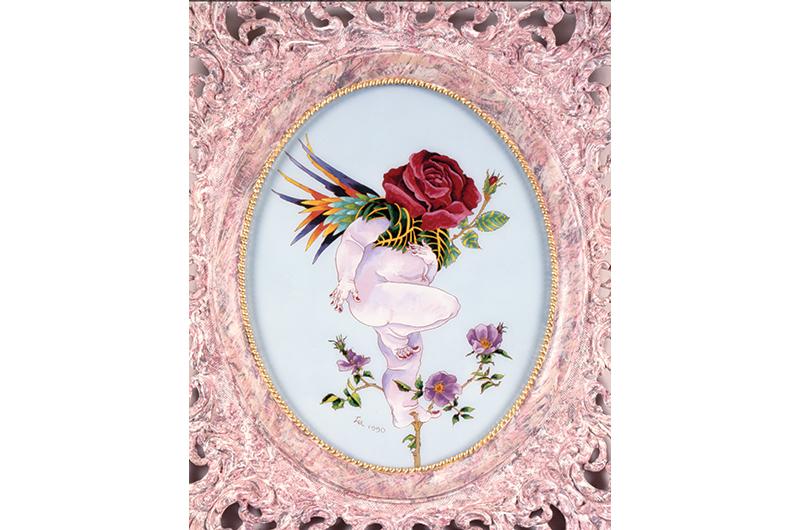

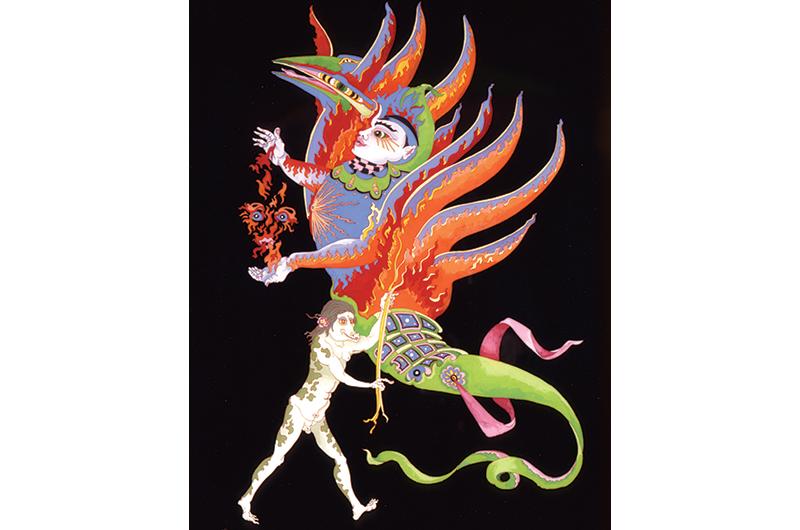

Lee was a master of reverse glass painting, an unusual style that traces back to the third century C.E. His subjects were often even older and more obscure: a fantasia of mythological, folkloric, zoomorphic figures whimsically reimagined in vibrant color. In the world of Richard Lee, frogs wore high heels and fish flew through the sky. Voluptuousness of all sorts, including fruit, was celebrated. The strawberry in particular played a role throughout his oeuvre, as did the rose. Sometimes they were found intertwined, as organic parts of human forms.

“The subject matter? Where does it come from?” he once wrote in an artist’s statement, “Words from the Painter’s Eye.” “It comes from Mother Nature, it comes from the seeds of Father Nature, and it comes from the human nature of all of us. The collective unconscious has a thriving history of symbols that vibrate the threads of all life.”

Richard Eugene Lee was born in 1933 in rural Pullman, Washington, and was raised as a farm boy, but there is some evidence that farming was not a comfortable fit for him. As his grandmother once said, “I don’t know where you got your ideas from, Richie, but it wasn’t from any of us.” The family was not religious, but Lee’s grandfather practiced the somewhat mystical art of dowsing to search for underground water, which seemed magical to a young boy.

Off the farm he went to Washington University, before receiving a scholarship to Jacob’s Pillow, a dance center in the Berkshires, and another to Bennington College in Vermont. (Though it remained at that time an all-girls school, the modern dance program needed male dancers.) By 1955, the twenty-two-year-old had danced as a love slave in Salomé at the old Metropolitan Opera in New York and studied under legendary pioneers in the modern dance world, including Martha Graham and Ruth St. Denis. But what jumps out when looking at a chronology of his life before he turned to painting is the time he spent in Alabama using his dance skills as a pioneering dance therapist nurturing the mentally ill – not the norm for a young dancer having success in New York City.

In 1955 he spent the summer at the Edgar Cayce Foundation in Virginia Beach. His notes say he studied at the Association for Research and Enlightenment. Cayce was a clairvoyant whose trances gave him access, he believed, to his luminous inner self.

As with dance, achievements in the art world started early. Lee had gallery shows beginning at the age of twenty-four, the year he began reverse glass painting. His first one-man show was in 1963 at the Setay Gallery in Beverly Hills. More were to follow in Munich, Paris, Los Angeles, Aspen, Baltimore, and New York. Some shows featured furniture pieces he had embellished or his fascination with the transformative nature of masks, a subject that would lead him across the country to work with western Native American tribes and collect feathers with Inuit villagers in Alaska. But it was his paintings that set him apart and best captured his attention. He would go on to complete more than 600 throughout the course of his life.

In “Words from the Painter’s Eye,” Lee described the technique: “Years ago I lived in a house where I was inspired to paint a motto over the bathtub which read ‘once upon a time is enough.’ The motto helps explain why I’ve chosen reverse glass painting as a medium of expression. For the technique of reverse painting, ‘foresight’ is the all-important guide.

“Details are painted first, and the backgrounds last; no opportunity exists to alter, take away, or add changes to the painted surface. The first drops of paint take their place in the picture and no amount of over-paint will show upon the front of the glass. You get the picture at once....Within the learning process of painting in reverse, ‘acceptance’ becomes the important factor in seeing the finished picture. I cannot change the picture.”

To create each painting, Lee would draw a “cartoon,” or sketch, of the figures on vellum, which he placed under the glass as a guide to outline the figures. From there, he would apply the remaining details and finally the background, literally working in reverse from the norm. It was a meticulous, obsessive process, particularly because the painting would never again be seen as the artist saw it while creating. When finished, he would turn it over and place it in its waiting frame with the painted side in, the reverse side facing the world.

But for Lee, the true start of each piece was the frame, itself a work of art that often inspired the work it would enclose. He preferred to paint on antique, somewhat rippled glass that made his images appear to move slightly, and often found the frames himself by scouring estate sales and thrift stores. If a frame was not in perfect condition, he would use skills obtained in Los Angeles in the mid-1950s when, employed as a finisher, he created faux and fantasy finishes for an exclusive line of wall décor and custom frames.

This L.A. period was key to the amazing fantasies he later made on Martha’s Vineyard from old, staid wood furniture. From 1997 to 2001, he showed these creations at the sumptuous antiques and art gallery Chicamoo, which he created with master wood sculptor Simon Hickman on Hickman’s Lambert’s Cove property in West Tisbury. In 2010 one of his furniture pieces was added to the permanent decorative arts collection at the Baltimore Museum of Art.

Though Lee would paint, gild, or apply faux-marbling technique to everything from side tables to coat racks, he particularly sought out cabinets, bookcases, and sideboards with glass fronts or panels. When his work was complete, the wooden portions of each piece, colorfully decorated fantasias beyond faux, no longer retained their wood-ish-ness, but became eye-vibrating frames complementing his reverse paintings on glass. Thus, an entire living room of furnishings, art, and décor could be a World of Richard Lee.

This is the environment he created for his own house, which also functioned as a studio, salon, and museum of sorts. In 1975 Lee was living in Aspen, Colorado, when he met jeweler Cheryl “CB” Stark, who extolled the virtues of the Island and persuaded him to visit. Over the next few years he set up the Dessert Gallerie and mask and painting studios in Vineyard Haven. Though mask making would call him away, he soon after returned to permanently settle on the Vineyard.

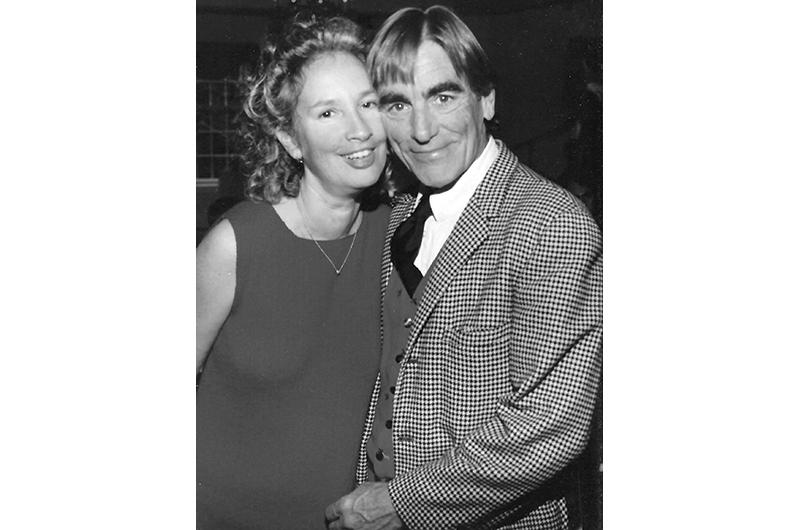

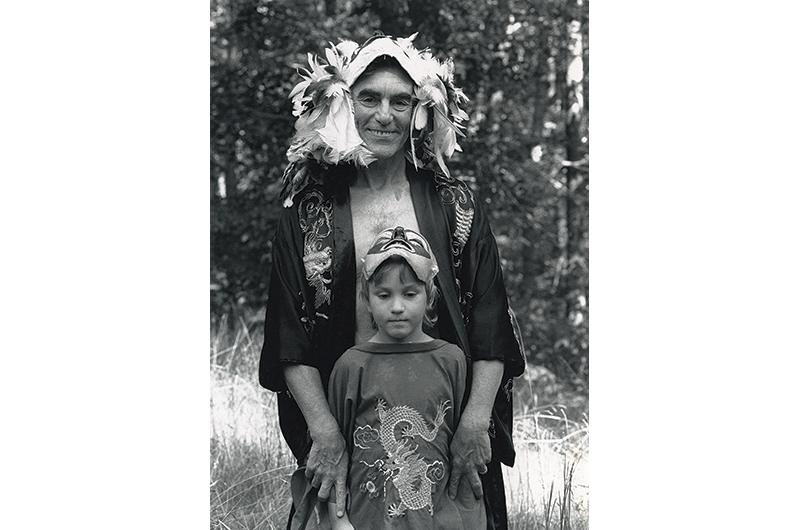

In 1982, he married Claudia Canerdy, known for her jewelry stores in Edgartown and Vineyard Haven. Son Hudson was born two years later. They set up a home in the Christiantown area of West Tisbury – a rambling structure that they built over time on land Lee cleared by hand and meticulously, lovingly tended. He filled the house with his designs and creations: gloriously painted furniture, luminously painted pastel walls, gilded animal skulls, masks, lush upholstery, carpets, and drapes.

In his daily and social life, the house was his own embellished frame and to be there was to be coddled in luxurious grand excess, suggesting an emperor’s palace, with the happy creator, a confident, funny, worldly, and curious man, offering coffees and desserts and rolling joints.

There are few non-geological, non-Wampanoag things on-Island that extend back 2,000 years. But in many ways, Lee’s provocative art and the universe he created can in fact be traced to an actual ancient emperor’s palace and the strange pagan art tradition buried therein.

The story begins in the late fifteenth century, when a series of caves was discovered across from the Colosseum in Rome. The walls and ceilings were covered with depictions of humans transformed, their bodies merged with other beings or stretched beyond possibility with extremities ending in floral cascades or heads sprouting vines. Mythological monsters coexisted with leering gargoyles and previously unknown beasts whose aspects contained all life forms. For the most part there was no sense of depth, each image existing in its unique decorative space. (With no alteration, the above descriptions could also be applied to Lee’s work.)

To the contemporary European eye, the images were seen as a pagan assault on a Christian establishment used to setting the rules of art. But they also captivated artists of the time and inspired pilgrimages. Michelangelo and Raphael crawled underground to study them. Nearly 300 years later, tourists Casanova and the Marquis de Sade scratched their signatures into a frescoed wall.

Eventually, it was determined that these were not caves but the buried Golden Palace of the Roman emperor Nero, who had commissioned the painter Fabullus to decorate the interior of his gilded home. Following Nero’s suicide at age thirty in 68 C.E., the palace was buried. Because the rooms were at first believed to be grotta, the Italian word for caves, the paintings they contained became known as “grotesque.”

Lee often employed the word to describe the figures in his paintings, including in a 2009 interview with Martha’s Vineyard Magazine. “It’s not the negative meaning of grotesque,” he asserted, “it has more to do with the interconnectedness of all things in nature.”

This is also the message of the Green Man, a pagan figure covered with leaves that inspired some of Lee’s work. The Green Man was so powerful in the European psyche that it survived the purging of non-Christian symbology. Images can be found throughout Europe, including in a series of stained glass windows in the Cathedral Notre-Dame in Paris.

Lee had a natural affinity with the Green Man and positioned a sculpture of the figure outside his house to look out over the grounds. Even Lee’s few landscapes had other-worldly qualities. He preferred inner-scapes and outer-scapes. Both are playful escapes from the literal, as Lee was supremely wont to do.

In “Notes from the Painter’s Eye,” he wrote: “If I have a desire for the paintings in the future it is to stimulate the hearts of passion into greater tolerance and compassion for individuals and individual cultures. Paintings can have the power to instruct the heart. That’s why I paint them.”

It was a sentiment that extended to all aspects of his life. For a certain set, one of Lee’s greatest gifts to the Island was the Crossover Ball, a New Year’s Eve celebration that occurred five times between 1994 and 2005 and bounced between the Martha’s Vineyard Playhouse in Vineyard Haven and the Hot Tin Roof in Edgartown. In Lee’s hands, the traditional crossover theme was embellished to include us, the partiers. In keeping with his advanced sense of mutability, this was an invitation to cross over genderwise. I found my personality changed when wearing a dress. According to my wife Joan, “You became demure.” Joan, meanwhile, having crossed into the animal kingdom, was presenting as a bear, which Lee enjoyed.

In many ways I saw my friend as a Green Man – a pagan artist worshipper of the unity of life who reveled in the visual and sensual greatness of existence. He still shares that delight with all who are willing to look into the art he framed for us.

While visiting with Lee’s family recently and leafing through his papers, his wife presented me with a Xeroxed fragment of an interview that Lee gave before moving to the Island. In it, I found the following statement: “There has always been a certain amount of controversy about my paintings. It’s because I’m actually three thousand years old.”

1 comment

1 comment

Comments (1)