Eight-legged, tiny, and hungry, every tick goes through life in search of blood. In most cases, their “search” for a host is rather passive: The familiar dog ticks and deer ticks of the Vineyard typically stake out a spot at the end of a piece of dune grass or lowbush blueberry and lie in wait. It may take months, but eventually an unsuspecting host – which could be as small as a mouse or as large as a horse – wanders by and the bloodthirsty critter jumps aboard.

But just when you thought you knew the enemy at the end of the twig, an imposter has arrived on the local arachnid scene. A washashore, if you will, and an impatient one at that.

“There’s a new tick [here] called the lone star tick,” says Dick Johnson of Oak Bluffs, a field biologist with the Martha’s Vineyard Tick-Borne Illness Reduction Initiative. Named for the distinctive white spot females have on their backs, its origins remain mysterious. Lone star ticks were found in New Jersey some thirty years ago, and have cropped up in other northeastern areas including Prudence Island in Narragansett Bay, Long Island, and southeastern Massachusetts. Johnson found the lone star tick on Chappaquiddick last September, and has found another in Chilmark.

“I was like, ‘What the heck is this?’” he recalls. “That’s certainly been an eye-opener for me.”

How the first lone star tick arrived on the Vineyard is anyone’s guess: It could have been transported here by a pet, a bird, a person, or via some combination of vectors. However it arrived, the lone star tick’s presence may indicate that this tick is taking hold on the Island. Stephen Rich, professor of microbiology and director of the Laboratory of Medical Zoology at the University of Massachusetts–Amherst notes that a tick cannot be considered established in an area until it has been found in all three of its life stages. This hasn’t happened on the Island, and officially the tick is still a non-resident species. But, Rich speculates, “They look established and here to stay.”

One more variety of tick in the woods might not seem like news in the county with the densest deer population, and – one could then infer – densest tick population in the state. But Rich points out that the lone star tick brings with it some decidedly un-ticklike habits.

“It’s a very different species: the way it attaches, its different mouthparts, the way it gets to hosts,” Rich says. In short, lone star ticks are much more aggressive and will actively pursue an animal. “Instead of just hanging out and waiting for something to come by, they’ll chase you down,” he explains. Apparently, somewhere along the way the lone star tick missed the “slow down you’re not off-Island anymore” bumper stickers.

There is something to like about lone star ticks, however: They do not carry Lyme disease. Lyme, as everyone on the Island surely knows well by now, is carried by the minute deer tick and causes a range of flu-like symptoms that can progress into serious arthritic and neurological complications. According to the national Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Lyme is the most commonly reported vector-borne illness in the country, despite the fact that 96 percent of reported cases occur in just thirteen states. Massachusetts is one of those states, and the Vineyard, Nantucket, and Cape Cod consistently rank near the top for the most reported incidence of Lyme within the Commonwealth.

So it’s good news indeed that the new tick doesn’t carry Lyme. That relief is somewhat tempered, however, by the fact that lone star ticks are vectors for no fewer than seven other known diseases, according to Sam Telford, professor of infectious disease at Tufts University’s Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine. Telford is part of the Martha’s Vineyard Tick-Borne Illness Reduction Initiative and is quick to add that not all of these diseases would be present in an area with a new infestation of lone star ticks.

“No tick bite is a good tick bite,” he sums up. He’s not kidding. In addition to Lyme, the all-too familiar deer ticks carry four known diseases that can be transmitted to humans, including babesiosis and anaplasmosis, which can be contracted at the same time as Lyme disease. Their larger cousins, dog ticks (also called wood ticks), carry two more: tularemia and Rocky Mountain spotted fever, which are also part of the lone star tick’s disease resumé. Adding the rest of the lone star tick’s brew to the mix brings the number of serious diseases associated with the tick population on the Island to at least eight and possibly as high as eleven. There are, as Stephen Rich of the University of Massachusetts puts it, “scads and scads of things in the ticks.”

For what it’s worth, ticks come into the world innocent and free of disease. Even the bacterial cause of Lyme disease, Borrelia burgdorferi, which was identified in 1982, is not inherent to the arachnids. When deer tick larvae hatch, they are about the size of a period at the end of a sentence. Too tiny to range much beyond the leaf litter in a forested area, they seek a host that is also small and lives at ground level, such as a white-footed mouse. And it is the mouse, more often than not, that transmits the bacteria to the tick larvae. A tick’s transition between each of its three life stages – larvae, nymph, and adult – requires a blood meal and is another opportunity for a tick to become infected.

What pathogens ticks end up with depends, therefore, on what pathogens their various hosts are carrying. This can vary regionally. Incidence rates of Lyme appear to be steady across Massachusetts’ deer tick populations: roughly 20 to 30 percent of nymphal-stage deer ticks are infected with Borrelia burgdorferi, regardless of where in the state they’re found. Stephen Rich and the team at the UMass–Amherst Laboratory of Medical Zoology are in the process of mapping out where in the Commonwealth ticks carrying different pathogens are found, by offering an important service for people who have found a tick on themselves: Using a simple form, anyone can send in their tick specimen and the lab will analyze it for pathogens.

For the past several summers, Rich and a team of university students have worked on the Cape and Islands in collaboration with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Barnstable County Extension, attempting to determine where ticks pick up co-infections and, in so doing, learn more about the ecology of the pathogens that cause human disease. The group traps small mammals at sites throughout the area, and analyzes animals and their attached ticks for pathogens. Early results appear to reconfirm the white-footed mouse as the main reservoir.

As with the larvae, nymphal ticks can take blood meals from mice. But they are also more mobile and able to find bigger mammals to feed on. Once a nymph molts into an adult tick, it needs the largest blood meal of all to facilitate reproduction. For deer and lone star ticks the usual reproductive host is deer; the reproductive hosts for dog ticks, despite their name, are skunks and raccoons. In addition to smaller animals and birds, the lone star tick has been known to feed on deer in all three of its life stages.

And there are plenty of deer. An aerial survey conducted in January 2013 found that there are about five thousand deer on the Island, approximately fifty animals per square mile. By contrast, the state Division of Fisheries and Wildlife reports that parts of western and central Massachusetts have ten to twelve deer per square mile. Deer tick population is thought to correlate with deer population: Theoretically a deer can have no ticks on it, but Telford says he’s seen as many as three hundred on one animal.

Besides being a food source, the deer is also where adult male and female ticks meet, greet, and mate. Once on the deer, male ticks take a small blood meal, mate, and die. The female’s job, on the other hand, is to mate and lay eggs before she dies, so her blood meal is about two hundred times her body weight, in order to provide the energy needed to produce a new generation of ticks. To concentrate the blood’s protein, the female tick squeezes all of the water out of the blood and secretes the liquid out her back end.

“It’s milliliters of blood,” says Rich. “Not a lot, but compared to the size of the tick it’s huge….They’re very efficient eating machines.”

Lyme and other tick-born illnesses have been a recognized part of life on the Vineyard for more than a quarter of a century. Surprisingly, however, the scope of the problem is only now coming into focus in a quantifiable way as early results from a five-year study begin to trickle in. The study is part of the Tick-Borne Illness Reduction Initiative, a grant-funded education, advocacy, and research project that started in 2010 as a collaboration between boards of health from each Island town. “[In the past] there was a lot of anecdotal information,” says co-chair of the initiative, Edgartown Health Agent Matt Poole. “You know, everyone and their brother – people had been treated for Lyme but the statistics rarely showed the number of cases that we all just knew amongst our family and friends.”

Poole, his wife, and two of his three children have had Lyme. “If you talk to Vineyarders that’s the case with just family after family,” he says.

At Vineyard Medical Services, a walk-in clinic in Vineyard Haven, there has been a steady stream of patients for years. “In the summer, it’s not unusual for us to see four to five or even eight cases of Lyme in a day,” says Dr. Gerry Yukevich, who works out of the clinic and is part of the boards of health initiative. Yet, almost unbelievably, as recently as 2011, the CDC reported only thirty patients per year on the Vineyard.

When the Island’s boards of health won the $250,000 grant from the Martha’s Vineyard Hospital in 2010 to start the Tick-Borne Illness Reduction Initiative, therefore, one of their first tasks was to seek a metric for the true number of cases on-Island. Their method was both clever and simple. “Over 90 percent of the doxy prescriptions written are to treat tick-borne illness,” explains Tisbury Health Commissioner Michael Loberg, co-chair of the initiative. Doxycycline is the main antibiotic for treating Lyme, and tracking its prescription over the previous two years indicated the CDC estimate was off by a factor of fifty. Instead of thirty cases a year, Loberg estimates the figure is closer to fifteen hundred, with notable spikes in June and July when deer tick nymphs are active, and in October and November when the adult ticks are feeding.

Part of the reason for the discrepancy between the number of reported cases and the number of prescriptions is that the CDC won’t confirm a case of Lyme without either the telltale bull’s eye or a positive blood test. There are various methods of testing for Lyme, but most won’t read positive for Lyme right after a person finds a tick bite. In order to stave off later effects of the disease, many Island physicians would rather not wait for a positive test to treat the disease. However, with early treatment a person may never test positive for Lyme disease.

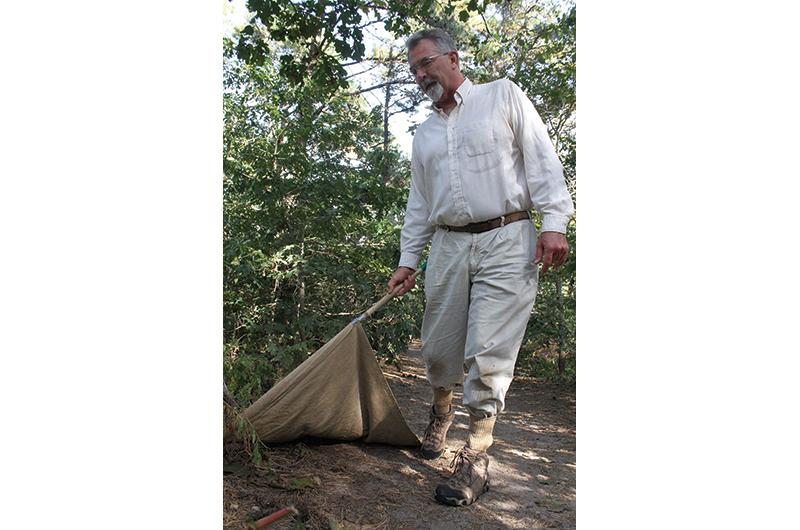

Of course, it’s best not to get a tick bite in the first place, but the overlap between human and tick habitat makes this a challenge. For several years researchers with the initiative have conducted yard surveys, analyzing homeowners’ lawns for tick activity. Work began on Chappaquiddick two summers ago, and moved to Chilmark this past summer. By dragging a large cloth flag through vegetation on the periphery of a yard, biologist Dick Johnson is able to measure the number of ticks that latch onto the fabric: In one Chilmark yard with a two-thousand-foot perimeter, he found an astonishing seventy ticks, all nymphs.

“Chilmark is the Island epicenter of the deer tick,” Johnson says. Yet he suspects Aquinnah is just as bad.

Tick habitat is actually increasing as the fields of the Island’s agricultural heyday revert to mixed woodland, where ticks get the shade and moisture they need to thrive. What’s more, ever since the Vineyard real estate boom of the 1970s, people have been steadily moving into deer tick country, driving up chances for a tick to find a human host. The truth is ticks and tick-borne diseases will exist on the Island as long as there are healthy woodlands full of wildlife.

“The fundamental thing to understand about Lyme, anaplasmosis [and] babesiosis is that they’re zoonosis,” says Stephen Rich, which is to say the illnesses are spillovers from the animal world. Unlike a human disease such as measles, which can be driven down in a population through vaccination, tick-borne pathogens will persist so long as ticks persist. “You’re not really losing the source, you’re just treating the disease,” he says.

One reason ticks are such potent vectors of disease is that they are often undetected. As a tick bites its host, its mouthparts release an anesthetic. Then, Rich says, they “cement” themselves to their host, which is why they can be so hard to pull off. The adult tick feeds for about 72 hours, during which time its saliva, bacteria and all, gets transmitted into the host. Nymph ticks generally feed for less time, but could still cause infection if they go undiscovered.

But what if every time a tick tried to bite a person they felt it and removed it before a pathogen was transmitted? For all his years out in the field studying ticks, Sam Telford has never had a tick-borne illness. “I’m allergic to their bites,” he says, “I itch like crazy. I know they’re there, so I can pull them off.”

This allergy phenomenon is being researched as a potential means to protect humans from contracting the disease. “What if everyone knew that they had a tick on them?” Telford asks. It’s a provocative question, especially now that there’s another tick with the potential to spread disease on the Island.

§§§§§§

LYME, CHRONIC LYME, AND THE LYME CENTER

“A lot of people say, ‘Do I have Lyme or do I not?’ and it’s not an easy answer,” says Island physician Gerry Yukevich. “One-third of people who have Lyme can’t recall when that little creature bit them.”

Complicating matters is the ongoing debate about the lingering effects of Lyme in some patients. Acute Lyme, or Lyme in its very early stages, is relatively clear-cut in its symptoms, diagnoses, and treatments, and most patients recover quickly if they are treated quickly. “The science on the acute phase is settled science,” says Tisbury Health Commissioner Loberg. “There’s agreement: ‘Here’s what you do.’”

Similarly there is little dispute about Post-treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome, which refers to the symptoms experienced by sufferers who do not recover fully or quickly, and still suffer from fatigue, sleep disorders, decreased concentration, and muscle and joint pain, months after they’ve finished a complete course of antibiotics.

Chronic Lyme is a term used by a growing number of physicians and patients who believe that the bacteria stays within the body, progressively impairing organ function and leading to a multitude of diverse symptoms both physical and neurological that could last a lifetime. With a variety of symptoms that could also be linked to other diseases or health concerns, the condition is not yet universally accepted by the medical community. This is why one West Tisbury family has made it their mission to raise awareness about Lyme disease and its potential long-term effects.

Enid Haller, her husband Sam Hiser, and their daughter, Bean, all suffer from what they are certain is chronic Lyme. They each contracted the disease either during their twenty years vacationing on the Island, or since they moved here six years ago. After years of frustration and misdiagnoses, they took action.

Four years ago Haller, who is a clinical psychologist, founded the Lyme support group, which meets once a month at Howes House in West Tisbury and has grown to include five-hundred members. She is also helping develop a Lyme-focused nursing curriculum at Cape Cod Community College that includes chronic Lyme in its curriculum. And in August 2012, the couple converted their guest home into the Lyme Center of Martha’s Vineyard, which provides resources and support for people suffering from the disease.

“We started the center because my daughter couldn’t get out of bed,” says Haller, “She missed her last month of class in school and they kept telling me, all the doctors kept saying she had mono.”

“There’s a serious vacuum of information for people,” Hiser adds. “What we did was [say], ‘Let’s hang a sign, create a phone number, provide an immediate resource.’