Artist Lanny McDowell has always been fascinated by birds. But it was the appearance of three unusual winged visitors to Menemsha Pond in early summer 2001 that set him on the path to become one of Martha’s Vineyard’s foremost birders and avian photographers. At the time the former art history major turned Island carpenter and part-time artist was living in West Tisbury. His friend Richard Cohen, who regularly raced his Herreshoff 12.5 on Menemsha Pond, knew that McDowell was knowledgeable about birds.

“He called to tell me that he’d seen some black-and-white duck-like birds that he hadn’t seen before and I ought to check them out,” McDowell recalled recently. McDowell hopped in his kayak. “I found these guys and I had my little camera with me and I shot over the bow and I got some pictures.”

It was a family of razorbills. Not uncommon to see in the winter off our coast, but very unusual for a species that was not known to nest farther south than on islands off the coast of northern Maine. McDowell called his friend, the late Vineyard Gazette bird columnist E. Vernon Laux. He was exuberant.

“In the long ornithological history of Massachusetts and Martha’s Vineyard, there has never been an occurrence like this,” Laux wrote in a story that ran on the front page of the Vineyard Gazette. Soon The New York Times got wind of the surprise visitors. Not for the first time, and certainly not the last, the national editorial hook was the Island’s reputation as a haven for celebrities – human versus avian.

“Rare Birds Eclipse Vineyard’s Celebrities” was published on August 26, 2001. Reporter Sara Rimer wrote, “To outsiders, this paradisiacal island off the coast of Massachusetts is known as a place to spot celebrities. This summer, the lineup has included Bill and Hillary Rodham Clinton, James Taylor, Carly Simon, Alan Dershowitz and Sarah Jessica Parker…To birders, the human species is the least of the excitement.”

The New York Times had sent a photographer along to the Vineyard, but a day sailing on the pond in search of razorbills came up empty. A photo was needed. McDowell had it, and The New York Times bought it.

With the sale of that one photo, McDowell saw an opportunity to do something that would be fun and satisfying: “As silly as it sounds after the fact, I thought to myself coyly, ‘This is a great way to make a living.’”

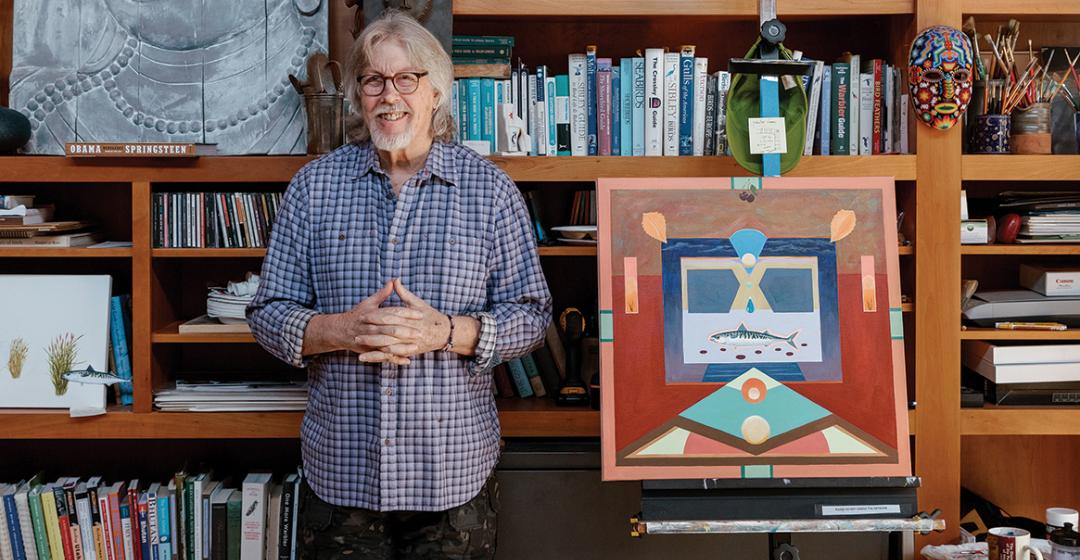

Which is not to say he immediately quit his various day jobs, of course. Or creating his paintings, which are mostly brightly colored, often geometric works of acrylic on canvas.

McDowell’s artistic creativity and appreciation of nature springs from a family tree rooted in outdoor pursuits and art. He grew up in the rural confines of Kent, Connecticut, one of a generation of family members – Harts, Moores, Lows, Youngs, and Peases – that summered in the Oak Bluffs family enclave on Nantucket Sound known as Harthaven, founded by William H. Hart, president of the Stanley Works in New Britain, Connecticut. There were so many artists among the various members of the clan in the middle of the twentieth century in Harthaven that informal family art shows were a regular feature of summer.

In 1970, McDowell and his wife were living in New Haven, where he had attended Yale University, when they decided to move to the Island to live year-round. What brought him back? “Everything I knew about the Vineyard from the past,” McDowell said.

Chilmark builder Emmett Carroll gave him his first job. He joined a crew building a house off Lighthouse Road in Gay Head (now Aquinnah). “I didn’t know the first thing about carpentry and Emmett just put up with my ignorance,” McDowell said. “It was a really cold winter with northwest exposure and that was my baptism to Island life in the wintertime.”

It was an introduction to year-round Island culture working with men only a few years older than he. Names familiar to a now aging generation of Islanders – Huey Taylor, Danny Larsen, Richard Greene – were part of the crew.

Soon, he used his newly acquired building skills to construct his own house – “hippie funk with some taste” – on family land at the end of Middle Point on Tisbury Great Pond, where his Harthaven relatives kept a rustic duck hunting camp. “I was definitely off the grid out there,” McDowell said.

Following the death of both his parents in the summer of 1983, he and his wife moved back to the family home in Kent overlooking the Housatonic Valley. He was working in real estate and hadn’t painted since college when his artistic genes stirred at the sight of deer against the landscape. “I would sit there, either with a spotting scope or binoculars, and watch the deer against the snow in the wintertime. And I said to myself, ‘I’m going to paint that scene.’” He’s been painting off and on ever since.

In 1995, recently divorced, he returned to the Island and carpentry. At the same time, his interest in birds, which had never waned, was amplified when he renewed his friendship with Laux. “All of a sudden I was off and running, tagging along with Vern, who was a moving force.”

Then, The New York Times flew in. “Instead of having a seasonal, very local audience, I thought I could have a year-round national audience for bird photographs, so I embarked on that project,” he said. “Unfortunately, my timing was terrible….There are a lot of birders out there with digital cameras.”

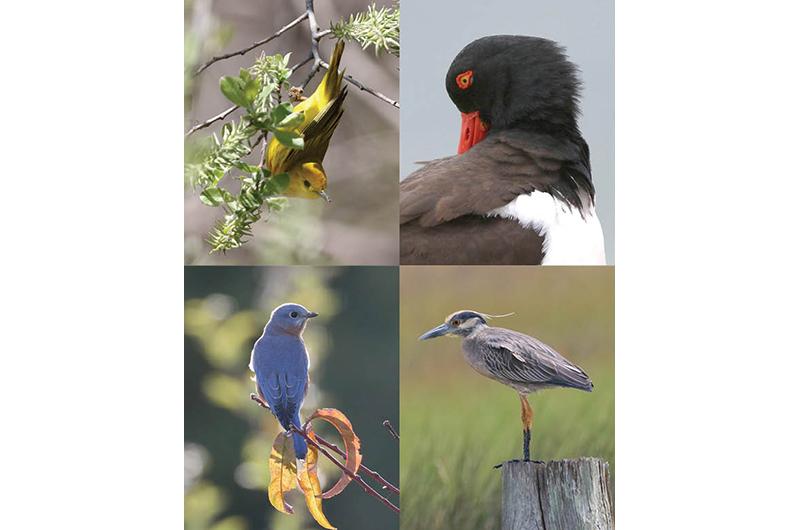

Their level of expertise became apparent in August 2004 when a wayward red-footed falcon visited the grass strip airfield in Katama. It was the first sighting of its species in North America, and it set the bird-watching world on fire. Birders flocked to the Island. Stalking the falcon with other photographers was when McDowell realized he would have to up his game. “I knew that to be a professional and have a satisfying result I would have to take it more seriously. I got a good camera and a good lens and birded more and shot more, and if I traveled, I took the camera with me.”

McDowell is low key about the photographs and paintings he sells off his website, lannymcdowellart.com, but he speaks with pride about Martha’s Vineyard Bird Alert, the “wildly successful” Facebook group he started in November 2010 that now boasts more than 3,200 members. “So I get around in the birding world, I spend a lot of time doing what I like to do,” he said. “I get a lot of exposure and I give away a lot of photographs to any Massachusetts nonprofit that wants them. It’s very satisfying. It takes up most of my so-called work time – it takes away from painting, for sure – but my exposure is large for being in a little pond.”

McDowell and his wife Melissa Keeler, whom he married in 2019, live on the west side of Tashmoo Pond in Vineyard Haven in a delightful rambling home with abundant nooks and crannies that house the couple’s eclectic collection of paintings, books, sculpture, decoys, and knick-knacks. They share this space with three cats, a Labrador retriever, a beagle, a boxer, and two French bulldogs that vie for the attention of any visitor.

On the walls hang McDowell’s artistic work, which includes a photo series of dolphins, paintings of waves, and a variety of abstract and representational paintings. Most recently, he has created a series of bird portraits he calls “Double Takes,” which he describes as “fanciful symmetries” in which the photo is flipped around a vertical axis to create a mirror image.

He has also stretched his wings and created a painted metal sculpture titled Hollow Man that sits outside the house welcoming visitors. The piece, which he said represents “the spirit of hope and encouragement,” started out as a painting until he thought to himself, “Why stop there?”

He said he knows a lot of people, whether it’s dealing with a camera or picking up paints, who say they’ve always wanted to do something creative but don’t know where to start. “They’re clearly afraid; they’re just afraid of making a mistake. But being afraid is like a dead-end street. What could you possibly be afraid of? I’m sure you could tell me, but does it have value enough to stand between you and the satisfaction of at least saying: I gave it a shot? It’s a little bit quirky but it’s mine.”

An uncompleted painting sat on the easel in his studio, waiting for a spell of bad weather, which is when McDowell said he gets most of his painting done. “And it better be bad weather that excludes going out to shoot birds, because I’m pretty much addicted to going out and shooting birds.”

He described his paintings as “about feeling good, projecting interesting creativity, and inspiring people, but they’re basically decoration. It’s décor.” In contrast, he said his photographs of birds and his ability to reach people on social media are intended to help a wider audience to understand the beauty and fragility of the natural world that is outside their window.

He is also passionate about a collaboration with his friend, pianist, and inventor David Stanwood of West Tisbury. The show, “Avian Improv: Martha’s Vineyard Edition,” features a sequence of 234 bird photos and an improvisational background track by Stanwood. “Avian Improv is sort of the current project that has the most promise of turning people on to birds, healing them, putting them at ease – any number of desirable adjectives that I want in my life and that I can make available,” he said.

The slideshow, available at mvmuseum.org/learn/ avianimprov, is intended as a way to make the photos and music available to a wider audience. He speaks enthusiastically about his hope that the project will someday supplant the visual version of elevator music: waiting room monitors tuned to cable news. It’s ideal for places such as hospitals and nursing homes, anyplace where people may not have the opportunity to be exposed to the “healing and contemplative power of nature,” he said.

For those more fortunate, the Island provides many wonderful opportunities to observe birds in their natural environment. One tip, he said, is to go out early, preferably at first light. His favorite birding locations include the Katama plains (“Specifically around the FARM Institute”), Norton Point Beach (“I never fail to have a good time just being out there”), the Sheriff’s Meadow Sanctuary off Plantingfield Way in Edgartown (“A great little bird mecca”), Aquinnah (“It has so much to offer in the fall in terms of being a funnel for migrating birds”), and Cape Pogue.

Being able to approach a bird or a flock without disrupting them and acquire a connection with what you’re photographing is a challenge, McDowell said.

“But when you’re done shooting, and you’re able to turn around and walk away almost as stealthily as you were when you approached the bird, that’s a kick. So you take home a great sense of your time being well-spent and respect for your subject matter. But it’s actually the experience of being there that is so gratifying.

“Being outdoors and being aware, it’s great medicine.”

2 comments

2 comments

Comments (2)